This is Part 1 of a four part miniseries on the process of speciation; how we get new species, how we can see this in action, and the end results of the process. This week, we’ll start with a seemingly obvious question: what is a species?

The definition of a ‘species’

‘Species’ are a human definition of the diversity of life. When we talk about the diversity of life, and the myriad of creatures and plants on Earth, we often talk about species diversity. This might seem glaringly obvious, but there’s one key issue: what is a species, anyway? While we might like to think of them as discrete and obvious groups (a dog is definitely not the same species as a cat, for example), the concept of a singular “species” is actually the result of human categorisation.

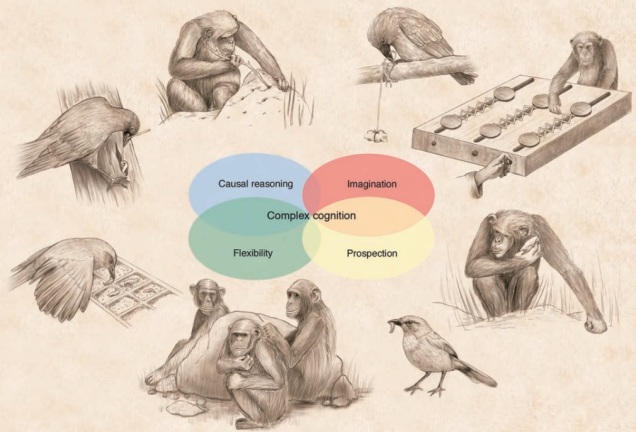

In reality, the diversity of life is spread across a huge spectrum of differentiation: from things which are closely related but still different to us (like chimps), to more different again (other mammals), to hardly relatable at all (bacteria and plants). So, what is the cut-off for calling something a species, and not a different genus, family, or kingdom? Or alternatively, at what point do we call a specific sub-group of a species as a sub-species, or another species entirely?

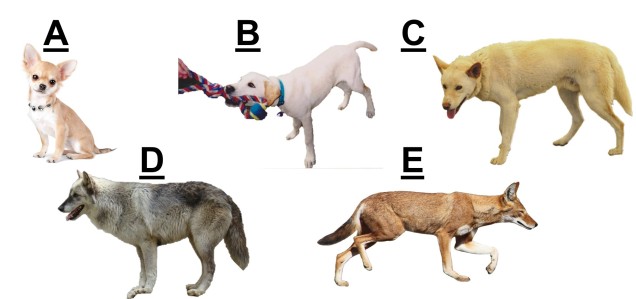

This might seem like a simple question: we look at two things, and they look different, so they must be different species, right? Well, of course, nature is never simple, and the line between “different” and “not different” is very blurry. Here’s an example: consider that you knew nothing about the history, behaviour or genetics of dogs. If you simply looked at all the different breeds of dogs on Earth, you might suggest that there are hundreds of species of domestic dogs. That seems a little excessive though, right? In fact, the domestic dog, Eurasian wolf, and the Australian dingo are all the same species (but different subspecies, along with about 38 others…but that’s another issue altogether).

How do we describe species?

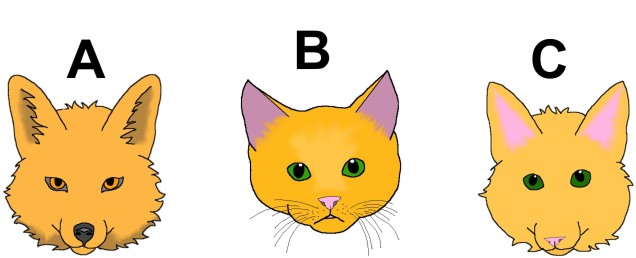

This method of describing species based on how they look (their morphology) is the very traditional approach to taxonomy. And for a long time, it seemed to work…until we get to more complex scenarios like the domestic dog. Or scenarios where two species look fairly similar, but in reality have evolved entirely differently for a very, very long time. Or groups which look close to more than one other species. So how do we describe them instead?

Believe it or not, there are dozens of ways of deciding what is a species and what isn’t. In Speciation (2004), Coyne & Orr count at least 25 different reported Species Concepts that had been suggested within science, based on different requirements such as evolutionary history, genetic identity, or ecological traits. These different concepts can often contradict one another about where to draw the line between species…so what do we use?

The Biological Species Concept (BSC)

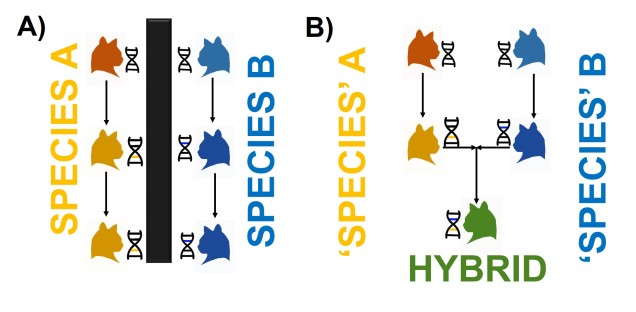

The most commonly used species concept is called the Biological Species Concept (BSC), which denotes that “species are groups of interbreeding natural populations that are reproductively isolated from other such groups” (Mayr, 1942). In short, a population is considered a different species to another population if an individual from one cannot reliably breed to form fertile, viable offspring with an individual from the other. We often refer to this as “reproductive isolation.” It’s important to note that reproductive isolation doesn’t mean they can’t breed at all: just that the hybrid offspring will not live a healthy life and produce its own healthy offspring.

For example, a horse and zebra can breed to produce a zorse, however zorse are fundamentally infertile (due to the different number of chromosomes between a horse and a zebra) and thus a horse is a different species to a zebra. However, a German Shepherd and a chihuahua can breed and make a hybrid mutt, so they are the same species.

You might naturally ask why reproductive isolation is apparently so important for deciding species. Most directly, this means that groups don’t share gene pools at all (since genetic information is introduced and maintained over time through breeding events), which causes them to be genetically independent of one another. Thus, changes in the genetic make-up of one species shouldn’t (theoretically) transfer into the gene pool of another species through hybrids. This is an important concept as the gene pool of a species is the basis upon which natural selection and evolution act: thus, reproductively isolated species may evolve in very different manners over time.

Pitfalls of the BSC

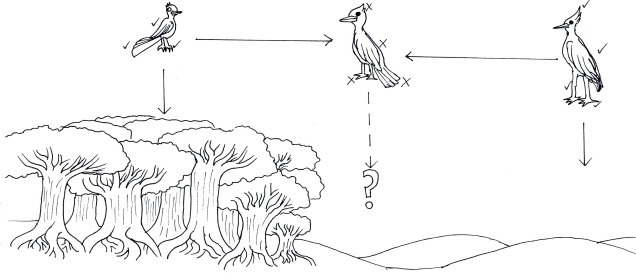

Just because the BSC is the most used concept doesn’t make it infallible, however. Many species on Earth don’t easily demonstrate reproductive isolation from one another, nor does the concept even make sense for asexually reproducing species. If an individual reproduced solely asexually (like many bacteria, or even some lizards), then by the BSC definition every individual is an entirely different species…which seems a little excessive. Even in sexually reproducing organisms, it can be hard to establish reproductive isolation, possibly because the species never come into contact physically.

This raises the debate of whether two species could, let alone will, hybridise in nature, which can be difficult to determine. And if two species do produce hybrid offspring, assessing their fertility or viability can be difficult to detect without many generations of breeding and measurements of fitness (hybrids may not be sustainable in nature if they are not well adapted to their environment and thus the two species are maintained as separate identities).

Integrative taxonomy

To try and account for the issues with the BSC, taxonomists try to push for the usage of “integrative taxonomy”. This means that species should be defined by multiple different agreeing concepts, such as reproductive isolation, genetic differentiation, behavioural differences, and/or ecological traits. The more traits that can separate the two, the greater support there is for the species to be separated: if they disagree, then more information is needed to determine exactly whether or not that should be called different species. Debates about taxonomy are ongoing and are likely going to be relevant for years to come, but form critical components of understanding biodiversity, patterns of evolution, and creating effective conservation legislation to protect endangered or threatened species (for whichever groups we decide are species).