Direction of evolution

We’ve talked previously on The G-CAT about how the genetic underpinning of certain evolutionary traits can change in different directions depending on the selective pressure it is under. Particularly, we can see how the frequency of different alleles might change in one direction or another, or stabilise somewhere in the middle, depending on its encoded trait. But thinking bigger picture than just the genetics of one trait, we can actually see that evolution as an entire process works rather similarly.

Divergent evolution

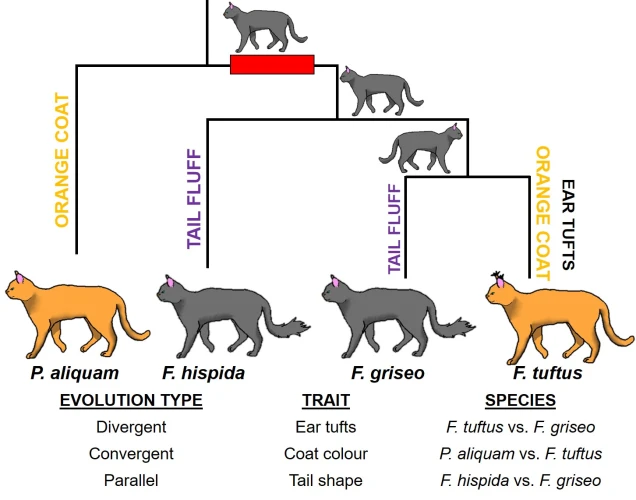

The classic view of the direction of evolution is based on divergent evolution. This is simply the idea that a particular species possess some ancestral trait. The species (or population) then splits into two (for one reason or another), and each one of these resultant species and populations evolves in a different way to the other. Over time, this means that their traits are changing in different directions, but ultimately originate from the same ancestral source.

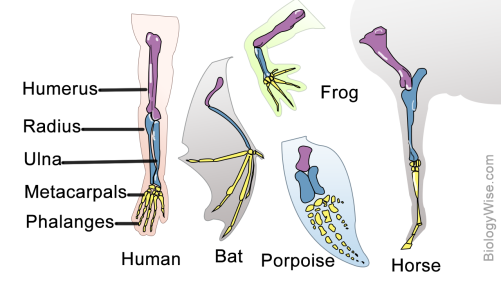

Evidence for divergent evolution is rife throughout nature, and is a fundamental component of all of our understanding of evolution. Divergent evolution means that, by comparing similar traits in two species (called homologous traits), we can trace back species histories to common ancestors. Some impressive examples of this exist in nature, such as the number of bones in most mammalian species. Humans have the same number of neck bones as giraffes; thus, we can suggest that the ancestor of both species (and all mammals) probably had a similar number of neck bones. It’s just that the giraffe lineage evolved longer bones whereas other lineages did not.

Convergent evolution

But of course, evolution never works as simply as you want it to, and sometimes we can get the direct opposite pattern. This is called convergent evolution, and occurs when two completely different species independently evolve very similar (sometimes practically identical) traits. This is often caused by a limitation of the environment; some extreme demand of the environment requires a particular physiological solution, and thus all species must develop that trait in order to survive. An example of this would be the physiology of carnivorous marsupials like Tasmanian devils or thylacines: despite being in another Class, their body shapes closely resemble something more canid. Likely, the carnivorous diet places some constraints on physiology, particularly jaw structure and strength.

A more dramatic (and potentially obvious) example of convergent evolution would be wings and the power of flight. Despite the fact that butterflies, bees, birds and bats all have wings and can fly, most of them are pretty unrelated to one another. It seems much more likely that flight evolved independently multiple times, rather than the other 99% of species that shared the same ancestor lost the capacity of flight.

Parallel evolution

Sometimes convergent evolution can work between two species that are pretty closely related, but still evolved independently of one another. This is distinguished from other categories of evolution as parallel evolution: the main difference is that while both species may have shared the same start and end point, evolution has acted on each one independent of the other. This can make it very difficult to diagnose from convergent evolution, and is usually determined by the exact history of the trait in question.

Parallel evolution is an interesting field of research for a few reasons. Firstly, it provides a scenario in which we can more rigorously test expectations and outcomes of evolution in a particular environment. For example, if we find traits that are parallel in a whole bunch of fish species in a particular region, we can start to look at how that particular environment drives evolution across all fish species, as opposed to one species case studies.

Following from that logic, it is then important to question the mechanisms of parallelism. From a genetic point of view, do these various species use the same genes (and genetic variants) to produce the same identical trait? Or are there many solutions to the selective question in nature? While these questions are rather complicated, and there has been plenty of evidence both for and against parallel genetic underpinning of parallel traits, it seems surprisingly often that many different genetic combinations can be used to get the same result. This gives interesting insight into how complex genetic coding of traits can be, and how creative and diverse evolution can be in the real world.

Where is evolution going?

So, where is evolution going for nature? Well, the answer is probably all over the place, but steered by the current environmental circumstances. Predicting the evolutionary impacts of particular environmental change (e.g. climate change) is exceedingly difficult but a critical component of understanding the process of evolution and the future of species. Evolution continually surprises us with creative solution to complex problems and I have no doubt new mysteries will continue to be thrown at us as we delve deeper.