“Pygmy perch swam across the desert”

As regular readers of The G-CAT are likely aware, my first ever scientific paper was published this week. The paper is largely the results of my Honours research (with some extra analysis tacked on) on the phylogenomics (the same as phylogenetics, but with genomic data) and biogeographic history of a group of small, endemic freshwater fishes known as the pygmy perch. There are a number of different messages in the paper related to biogeography, taxonomy and conservation, and I am really quite proud of the work.

To my honest surprise, the paper has received a decent amount of media attention following its release. Nearly all of these have focused on the biogeographic results and interpretations of the paper, which is arguably the largest component of the paper. In these media releases, the articles are often opened with “…despite the odds, new research has shown how a tiny fish managed to find its way across the arid Australian continent – more than once.” So how did they manage it? These are tiny fish, and there’s a very large desert area right in the middle of Australia, so how did they make it all the way across? And more than once?!

The Great (southern) Southern Land

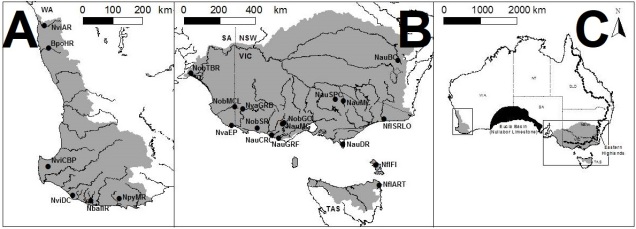

To understand the results, we first have to take a look at the context for the research question. There are seven officially named species of pygmy perches (‘named’ is an important characteristic here…but we’ll go into the details of that in another post), which are found in the temperate parts of Australia. Of these, three are found with southwest Western Australia, in Australia’s only globally recognised biodiversity hotspot, and the remaining four are found throughout eastern Australia (ranging from eastern South Australia to Tasmania and up to lower Queensland). These two regions are separated by arid desert regions, including the large expanse of the Nullarbor Plain.

The Nullarbor Plain is a remarkable place. It’s dead flat, has no trees, and most importantly for pygmy perches, it also has no standing water or rivers. The plain was formed from a large limestone block that was pushed up from beneath the Earth approximately 15 million years ago; with the progressive aridification of the continent, this region rapidly lost any standing water drainages that would have connected the east to the west. The remains of water systems from before (dubbed ‘paleodrainages’) can be seen below the surface.

Biogeography of southern Australia

As one might expect, the formation of the Nullarbor Plain was a huge barrier for many species, especially those that depend on regular accessible water for survival. In many species of both plants and animals, we see in their phylogenetic history a clear separation of eastern and western groups around this time; once widely distributed species become fragmented by the plain and diverged from one another. We would most certainly expect this to be true of pygmy perch.

But our questions focus on what happened before the Nullarbor Plain arrived in the picture. More than 15 million years ago, southern Australia was a massively different place. The climate was much colder and wetter, even in central Australia, and we even have records of tropical rainforest habitats spreading all the way down to Victoria. Water-dependent animals would have been able to cross the southern part of the continent relatively freely.

Biogeography of the enigmatic pygmy perches

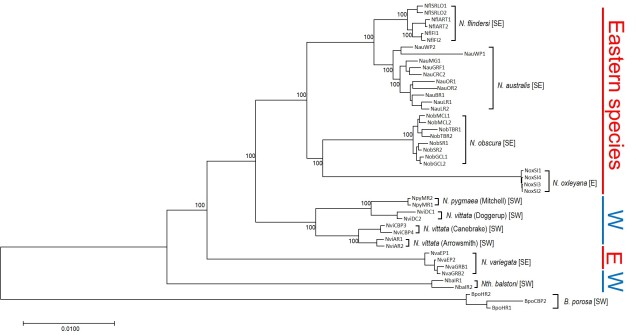

This is where the real difference between everything else and pygmy perch happens. For most species, we see only one east and west split in their phylogenetic tree, associated with the Nullarbor Plain; before that, their ancestors were likely distributed across the entire southern continent and were one continuous unit.

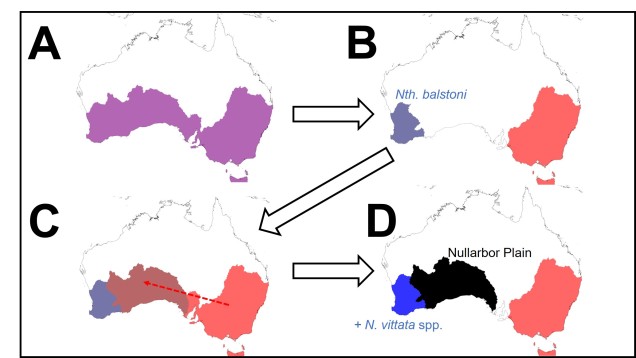

Not for pygmy perch, though. Our phylogenetic patterns show that there were multiple splits between eastern and western ancestral pygmy perch. We can see this visually within the phylogenetic tree; some western species of pygmy perches are more closely related, from an evolutionary perspective, to eastern species of pygmy perches than they are to other western species. This could imply a couple different things; either some species came about by migration from east to west (or vice versa), and that this happened at least twice, or that two different ancestral pygmy perches were distributed across all of southern Australia and each split east-west at some point in time. These two hypotheses are called “multiple invasion” and “geographic paralogy”, respectively.

So, which is it? We delved deeper into this using a type of analysis called ‘ancestral clade reconstruction’. This tries to guess the likely distributions of species ancestors using different models and statistical analysis. Our results found that the earliest east-west split was due to the fragmentation of a widespread ancestor ~20 million years ago, and a migration event facilitated by changing waterways from the Nullarbor Plain pushing some eastern pygmy perches to the west to form the second group of western species. We argue for more than one migration across Australia since the initial ancestor of pygmy perches must have expanded from some point (either east or west) to encompass the entirety of southern Australia.

So why do we see this for pygmy perch and no other species? Well, that’s the real mystery; out of all of the aquatic species found in southeast and southwest Australia, pygmy perch are one of the worst at migrating. They’re very picky about habitat, small, and don’t often migrate far unless pushed (by, say, a flood). It is possible that unrecorded extinct species of pygmy perch might help to clarify this a little, but the chances of finding a preserved fish fossil (let alone for a fish less than 8cm in size!) is extremely unlikely. We can really only theorise about how they managed to migrate.

What does this mean for pygmy perches?

Nearly all species of pygmy perch are threatened or worse in the conservation legislation; there have been many conservation efforts to try and save the worst-off species from extinction. Pygmy perches provide a unique insight to the history of the Australian climate and may be a key in unlocking some of the mysteries of what our land was like so long ago. Every species is important for conservation and even those small, hard-to-notice creatures that we might forget about play a role in our environmental history.

3 thoughts on “How did pygmy perch swim across the desert?”