This is Part 2 of a four part miniseries on the process of speciation: how we get new species, how we can see this in action, and the end results of the process. This week we’re taking a look at how new species are formed from natural selection. For Part 1, on the identity and concept of the species, click here.

The Origin of Species

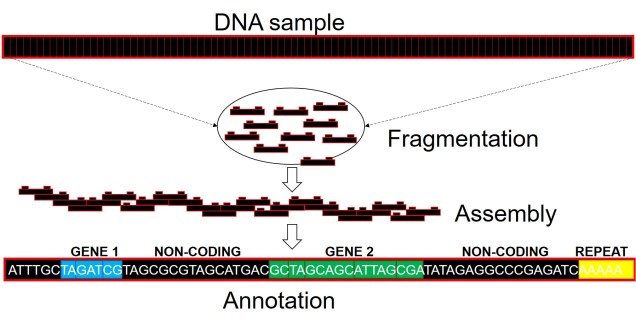

Despite Darwin’s scientifically ground-breaking revelations over 150 years ago, the truth of the origin of species has remained a puzzling and complex question in biology. While the fundamental concepts of Darwin’s theory remain heavily supported – that groups which become separated from one another and undergo differing evolutionary pathways through natural selection may over time form new species – the mechanisms leading to this are mysterious. Even though the heritable component of evolution (DNA) was not uncovered for a hundred years after publishing ‘On the Origin of Species’, Darwin’s theory can largely explain many patterns of the formation of species on Earth.

The population-speciation continuum

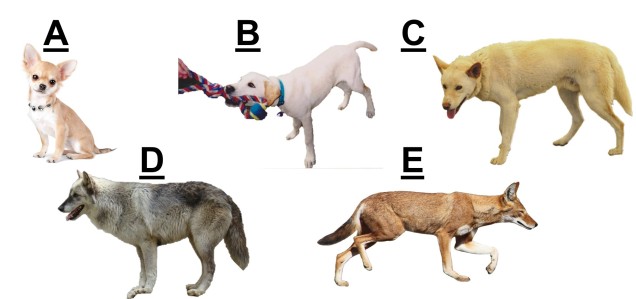

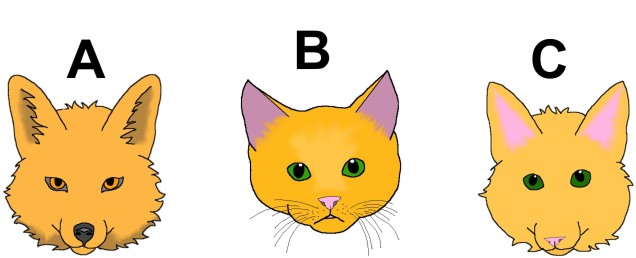

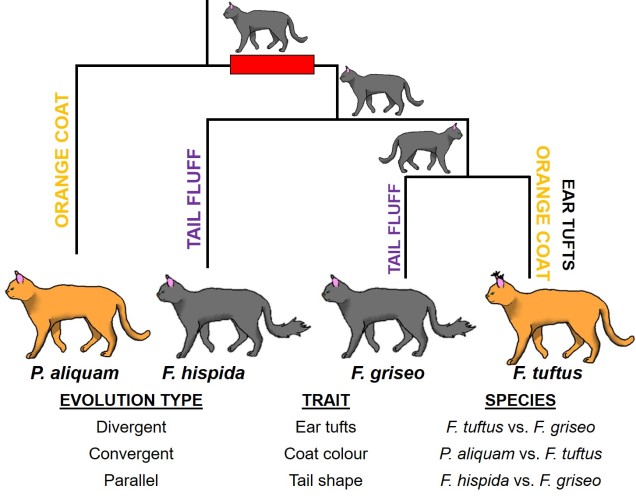

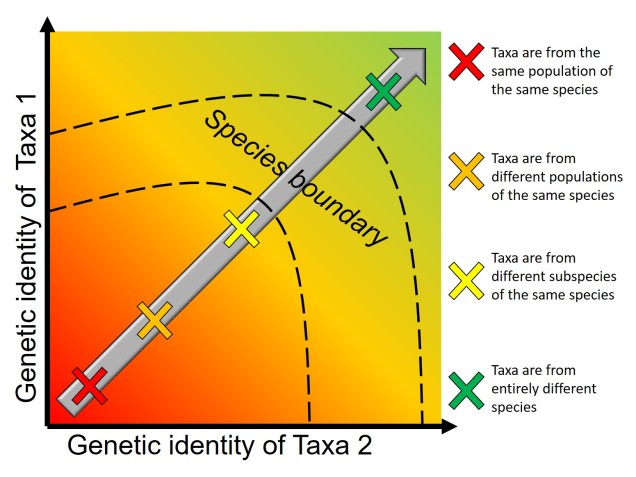

The understanding that groups that are separated progress into species through differential adaptation leads to a phenomenon as the ‘speciation continuum’: all populations exist at some point on the continuum, with those that are most differentiated (i.e. most progressed) are distinct species, whereas those least differentiated are closely related or the same population. Whether or not populations progress along this continuum, and how fast this progression happens, depends on the difference in selective pressure and speed of evolution in the populations. Even if two populations are physically separated, they might not necessarily form new species if the separation is too short-term or if they do not evolve in different ways. Even if they do differentially evolve, whether or not they develop reproductive isolation is not always consistent.

Furthermore, how these populations are changing may affect the rate or success of speciation: if the traits that evolve differently across the population also cause them to be unable to breed, then they may quickly become reproductively isolated and thus new species. For example, Momigliano et al. (2017) demonstrated the fastest known rate of speciation (within 3000 generations) in a marine vertebrate in a species of flounders. Flounders that adapted to a higher salinity environment became reproductively isolated from their sister population as their sperm could not tolerate the high salinity conditions (directly preventing breeding and causing reproductive isolation). This strong and rapid selection to an environment, and its subsequent selection on reproductive ability, was cutely described as a “magic trait”.

Modes of speciation

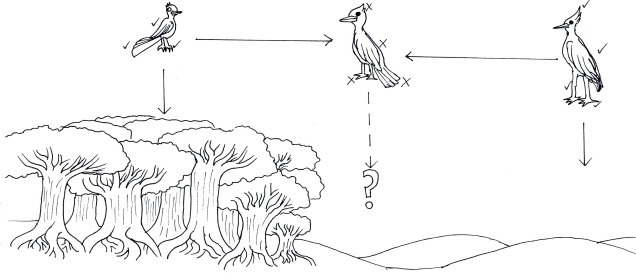

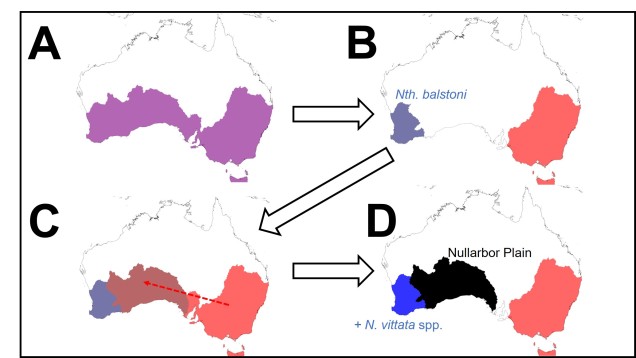

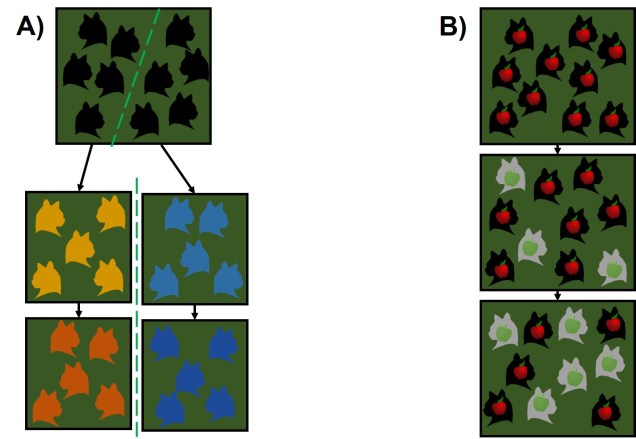

Darwin’s model of speciation describes what is called “allopatric speciation”, whereby physical separation of populations by some form of barrier (often attributed to changes such as climatic shifts, mountain range formations or island separation) isolates populations which then independently evolve until they reach a point of differentiation where they can no longer interbreed. Thus, they are now separate species (based on the Biological Species Concept, anyway). Allopatric speciation has traditionally believed to be the most common process of speciation, and is consistently used as the model for teaching and understanding speciation.

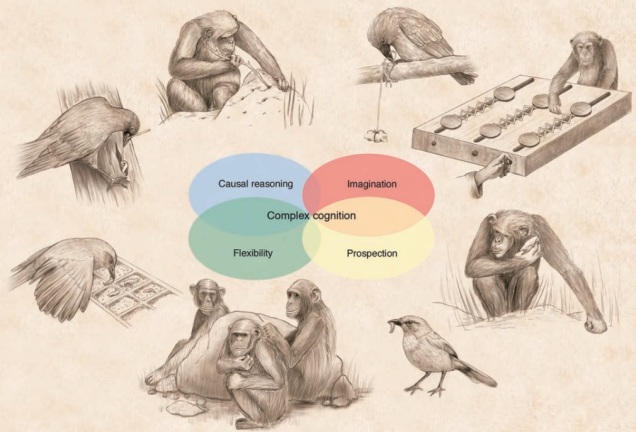

While this physical separation is the strongest and most immediately obvious method of speciation, other forms without geographic barriers have been documented. “Sympatric speciation” involves speciation events where there are no apparent geographical barriers that separate populations: instead, other factors may be driving their divergence from one another. This can relate to different microenvironments within the same area, where one population migrates and adapts to an environment which excludes the other population. This is referred to as “ecological speciation” and has been particularly noted within lake fish radiating into different habitats. There are a number of other mechanisms by which sympatric speciation could also occur, however, including temporal isolation (e.g. different flowering times in plants), sexual selection (e.g. a mutation leads to a new physiology that is more attractive to others with that physiology) or polyploidy (e.g. a ‘mutation’ causes an organism to have multiple copies of its genome, making it effectively reproductively isolated from its neighbours due to incompatible sex cells).

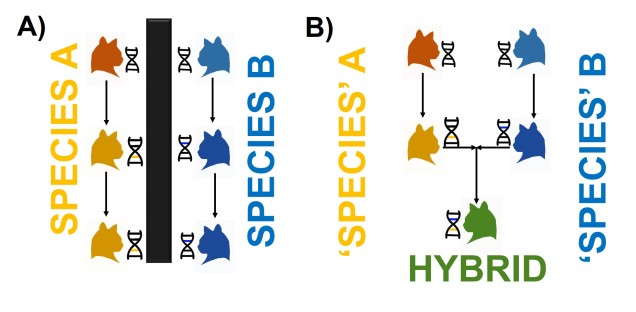

Sympatric speciation has received a great deal of controversy, due to the fact that some levels of gene flow could occur across the two populations with relative ease (compared to allopatric populations). This gene flow should cause the two populations to reconnect and prevent each population from evolving differently from one another (as changes in one population’s gene pool will be introduced into the other). Speciation with gene flow has been shown for some species, based on the idea that the pressure of natural selection (i.e. being adapted to the right habitat) is much stronger than the level of gene flow (i.e. the introduction of non-adapted genes from the other population), so the two populations still diverge genetically.

Gene flow across populations (through hybridisation) will balance out the different allele frequencies of the two gene pools, preventing adaptive alleles from moving towards fixation as per the standard natural selection process. While the effect of gene flow might slow the process, taking longer for the populations to diverge to the species level, speciation can still be achieved. Thus, the balance of gene flow and adaptive divergence is critical in determining whether ecological speciation is possible.

The reality of species

While the distinction between divergent populations and species might be a complex one, development in genomic technologies and greater understanding of evolutionary patterns is helping us uncover the real origin of species. And while species might not be as concrete a concept as one might expect, understanding the processes that generate new species and diversity is critical for understanding the diversity within nature that we see today, and also the potential diversity for the future (and why protecting said diversity is important!).