Scientific name

Octorokus infletus

Meaning: Octorokus from [octorok] in Hylian; infletus from [inflate] in Latin.

Translation: inflating octorok; all varieties use an inflatable air sac derived from the swim bladder to float and scan the horizon.

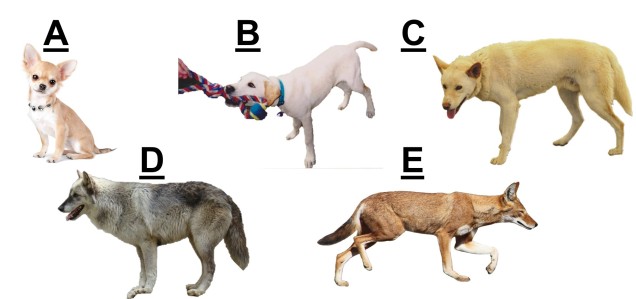

Varieties

Octorokus infletus hydros [aquatic morphotype]

Octorokus infletus petram [mountain morphotype]

Octorokus infletus silva [forest morphotype]

Octorokus infletus arctus [snow morphotype]

Octorokus infletus imitor [deceptive morphotype]

Common name

Variable octorok

Taxonomic status

Kingdom Animalia; Phylum Mollusca; Class Cephalapoda; Order Octopoda; Family Octopididae; Genus Octorokus; Species infletus

Conservation status

Least Concern

Distribution

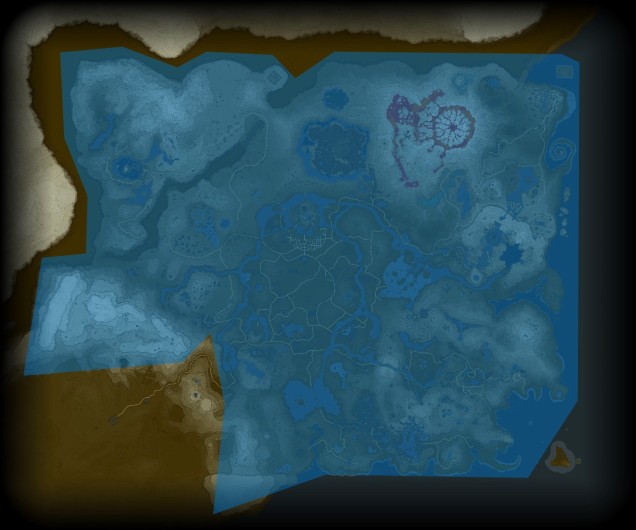

The species is found throughout all major habitat regions of Hyrule, with localised morphotypes found within specific habitats. The only major region where the variable octorok is not found is within the Gerudo Desert, suggesting some remnant dependency of standing water.

Habitat

Habitat choice depends on the physiology of the morphotype; so long as the environment allows the octorok to blend in, it is highly likely there are many around (i.e. unseen).

Behaviour and ecology

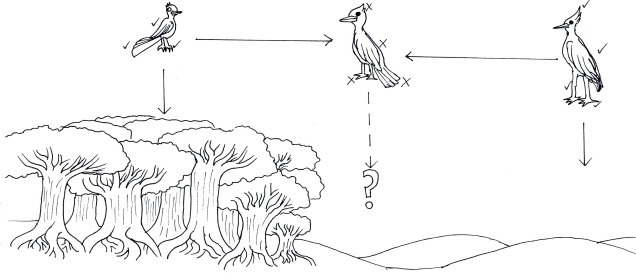

The variable octorok is arguably one of the most diverse species within modern Hyrule, exhibiting a large number of different morphotypic forms and occurring in almost all major habitat zones. Historical data suggests that the water octorok (Octorokus infletus hydros) is the most ancestral morphotype, with ancient literature frequently referring to them as sea-bearing or river-traversing organisms. Estimates from the literature suggests that their adaptation to land-based living is a recent evolutionary step which facilitated rapid morphological radiation of the lineage.

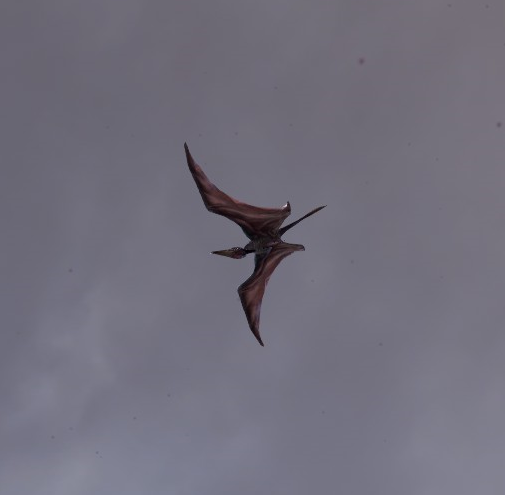

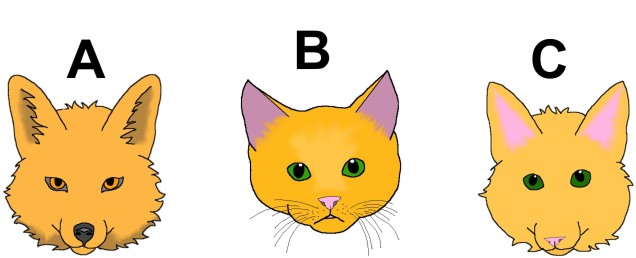

Several physiological characteristics unite the variable morphological forms of the octorok into a single identifiable species. Other than the typical body structure of an octopod (eight legs, largely soft body with an elongated mantle region), the primary diagnostic trait of the octorok is the presence of a large ‘balloon’ with the top of the mantle. This appears to be derived from the swim bladder of the ancestral octorok, which has shifted to the cranial region. The octorok can inflate this balloon using air pumped through the gills, filling it and lifting the octorok into the air. All morphotypes use this to scan the surrounding region to identify prey items, including attacking people if aggravated.

Diets of the octorok vary depending on the morphotype and based on the ecological habitat; adaptations to different ecological niches is facilitated by a diverse and generalist diet.

Demography

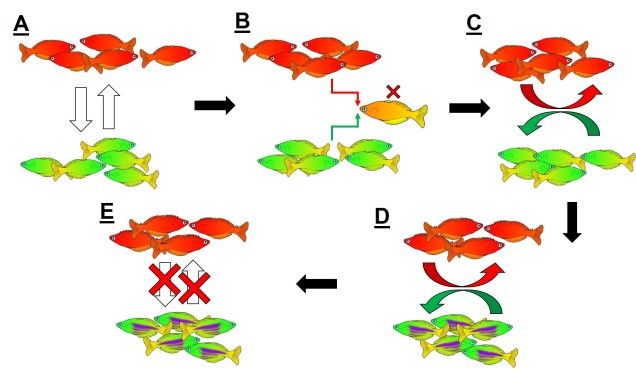

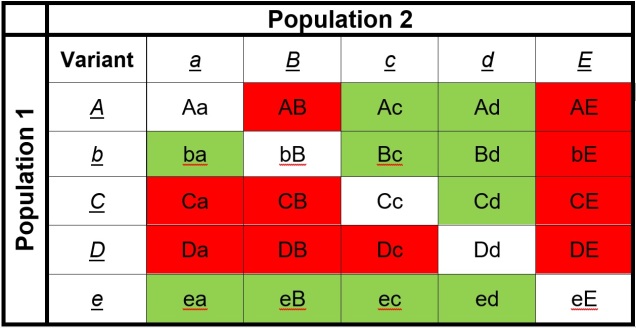

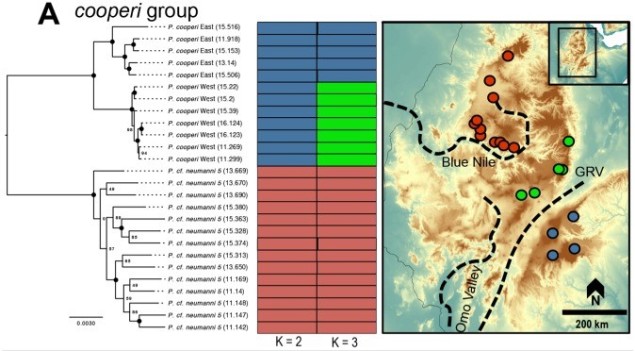

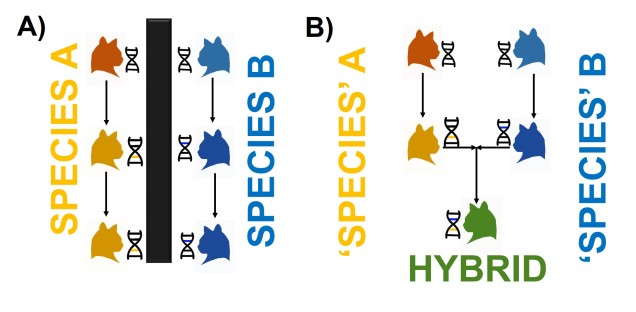

Although limited information is available on the amount of gene flow and population connectivity between different morphotypes, by sheer numbers alone it would appear the variable octorok is highly abundant. Some records of interactions between morphotypes (such as at the water’s edge within forested areas) implies that the different types are not reproductively isolated and can form hybrids: how this impacts resultant hybrid morphotypes and development is unknown. However, given the propensity of morphotypes to be largely limited to their adaptive habitats, it would seem reasonable to assume that some level of population structure is present across types.

Adaptive traits

The variable octorok appears remarkably diverse in physiology, although the recent nature of their divergence and the observed interactions between morphological types suggests that they are not reproductively isolated. Whether these are the result of phenotypic plasticity, and environmental pressures are responsible for associated physiological changes to different environments, or genetically coded at early stages of development is unknown due to the cryptic nature of octorok spawning.

All octoroks employ strong behavioural and physiological traits for camouflage and ambush predation. Vegetation is usually placed on the top of the cranium of all morphotypes, with the exact species of plant used dependent on the environment (e.g. forest morphotypes will use grasses or ferns, whilst mountain morphotypes will use rocky boulders). The octorok will then dig beneath the surface until just the vegetation is showing, effectively blending in with the environment and only occasionally choosing to surface by using the balloon. Whether this behaviour is passed down genetically or taught from parents is unclear.

Management actions

Few management actions are recommended for this highly abundant species. However, further research is needed to better understand the highly variable nature and the process of evolution underpinning their diverse morphology. Whether morphotypes are genetically hardwired by inheritance of determinant genes, or whether alterations in gene expression caused by the environmental context of octoroks (i.e. phenotypic plasticity) provides an intriguing avenue of insight into the evolution of Hylian fauna.

Nevertheless, the transition from the marine environment onto the terrestrial landscape appears to be a significant stepping stone in the radiation of morphological structures within the species. How this has been facilitated by the genetic architecture of the octorok is a mystery.