Allele frequency

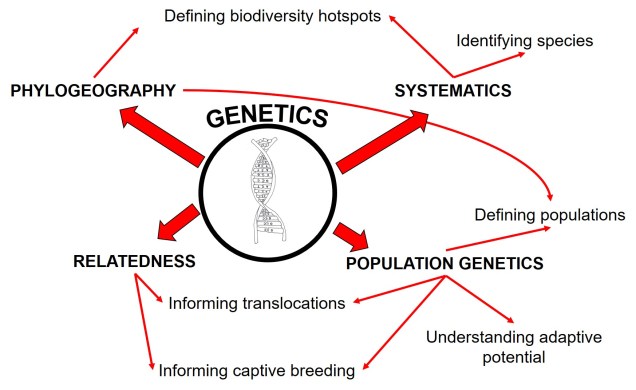

A number of times before on The G-CAT, we’ve discussed the idea of using the frequency of different genetic variants (alleles) within a particular population or species to test a number of different questions about evolution, ecology and conservation. These are all based on the central notion that certain forces of nature will alter the distribution and frequency of alleles within and across populations, and that these patterns are somewhat predictable in how they change.

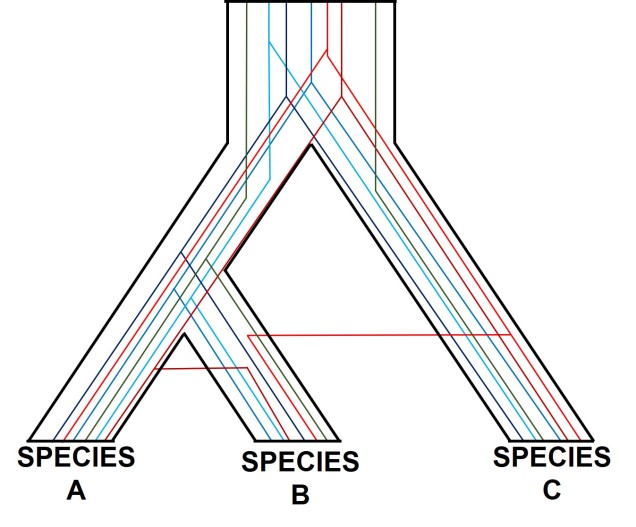

One particular distinction we need to make early here is the difference between allele frequency and allele identity. In these analyses, often we are working with the same alleles (i.e. particular variants) across our populations, it’s just that each of these populations may possess these particular alleles in different frequencies. For example, one population may have an allele (let’s call it Allele A) very rarely – maybe only 10% of individuals in that population possess it – but in another population it’s very common and perhaps 80% of individuals have it. This is a different level of differentiation than comparing how different alleles mutate (as in the coalescent) or how these mutations accumulate over time (like in many phylogenetic-based analyses).

Non-adaptive (neutral) uses

Testing neutral structure

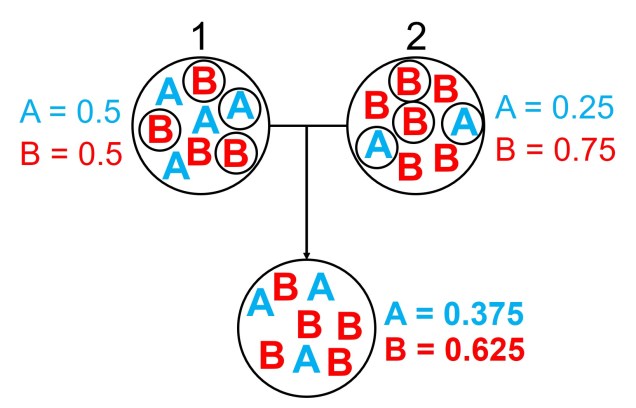

Arguably one of the most standard uses of allele frequency data is the determination of population structure, one which more avid The G-CAT readers will be familiar with. This is based on the idea that populations that are isolated from one another are less likely to share alleles (and thus have similar frequencies of those alleles) than populations that are connected. This is because gene flow across two populations helps to homogenise the frequency of alleles within those populations, by either diluting common alleles or spreading rarer ones (in general). There are a number of programs that use allele frequency data to assess population structure, but one of the most common ones is STRUCTURE.

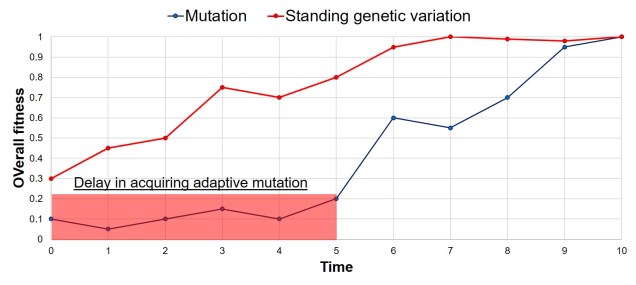

Determining genetic bottlenecks and demographic change

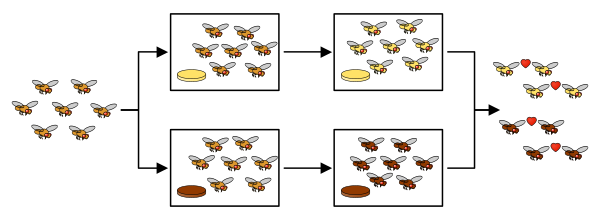

Other neutral aspects of population identity and history can be studied using allele frequency data. One big component of understanding population history in particular is determining how the population size has changed over time, and relating this to bottleneck events or expansion periods. Although there are a number of different approaches to this, which span many types of analyses (e.g. also coalescent methods), allele frequency data is particularly suited to determining changes in the recent past (hundreds of generations, as opposed to thousands of generations ago). This is because we expect that, during a bottleneck event, it is statistically more likely for rare alleles (i.e. those with low frequency) in the population to be lost due to strong genetic drift: because of this, the population coming out of the bottleneck event should have an excess of more frequent alleles compared to a non-bottlenecked population. We can determine if this is the case with tests such as the heterozygosity excess, M-ratio or mode shift tests.

Adaptive (selective) uses

Testing different types of selection

We’ve also discussed previously about how different types of natural selection can alter the distribution of allele frequency within a population. There are a number of different predictions we can make based on the selective force and the overall population. For understanding particular alleles that are under strong selective pressure (i.e. are either strongly adaptive or maladaptive), we often test for alleles which have a frequency that strongly deviates from the ‘neutral’ background pattern of the population. These are called ‘outlier loci’, and the fact that their frequency is much more different from the average across the genome is attributed to natural selection placing strong pressure on either maintaining or removing that allele.

Other selective tests are based on the idea of correlating the frequency of alleles with a particular selective environmental pressure, such as temperature or precipitation. In this case, we expect that alleles under selection will vary in relation to the environmental variable. For example, if a particular allele confers a selective benefit under hotter temperatures, we would expect that allele to be more common in populations that occur in hotter climates and rarer in populations that occur in colder climates. This is referred to as a ‘genotype-environment association test’ and is a good way to detect polymorphic selection (i.e. when multiple alleles contribute to a change in a single phenotypic trait).

Taxonomic (species identity) uses

At one end of the spectrum of allele frequencies, we can also test for what we call ‘fixed differences’ between populations. An allele is considered ‘fixed’ it is the only allele for that locus in the population (i.e. has a frequency of 1), whilst the alternative allele (which may exist in other populations) has a frequency of 0. Expanding on this, ‘fixed differences’ occur when one population has Allele A fixed and another population has Allele B fixed: thus, the two populations have as different allele frequencies (for that one locus, anyway) as possible.

Fixed differences are sometimes used as a type of diagnostic trait for species. This means that each ‘species’ has genetic variants that are not shared at all with its closest relative species, and that these variants are so strongly under selection that there is no diversity at those loci. Often, fixed differences are considered a level above populations that differ by allelic frequency only as these alleles are considered ‘diagnostic’ for each species.

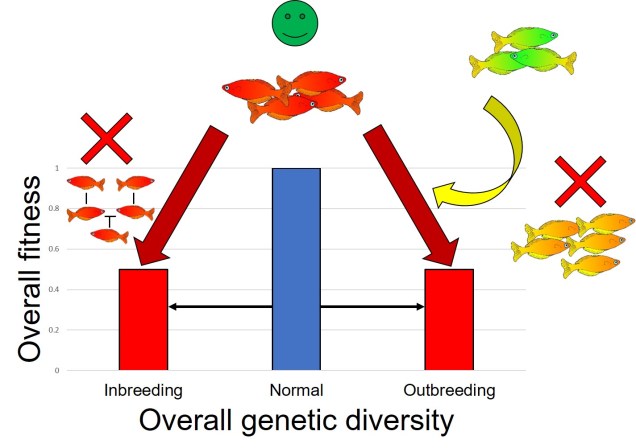

Intrapopulation (relatedness) uses

Allele frequency-based methods are even used in determining relatedness between individuals. While it might seem intuitive to just check whether individuals share the same alleles (and are thus related), it can be hard to distinguish between whether they are genetically similar due to direct inheritance or whether the entire population is just ‘naturally’ similar, especially at a particular locus. This is the distinction between ‘identical-by-descent’, where alleles that are similar across individuals have recently been inherited from a similar ancestor (e.g. a parent or grandparent) or ‘identical-by-state’, where alleles are similar just by chance. The latter doesn’t contribute or determine relatedness as all individuals (whether they are directly related or not) within a population may be similar.

To distinguish between the two, we often use the overall frequency of alleles in a population as a basis for determining how likely two individuals share an allele by random chance. If alleles which are relatively rare in the overall population are shared by two individuals, we expect that this similarity is due to family structure rather than population history. By factoring this into our relatedness estimates we can get a more accurate overview of how likely two individuals are to be related using genetic information.

The wild world of allele frequency

Despite appearances, this is just a brief foray into the many applications of allele frequency data in evolution, ecology and conservation studies. There are a plethora of different programs and methods that can utilise this information to address a variety of scientific questions and refine our investigations.