Spatial and temporal factors of speciation

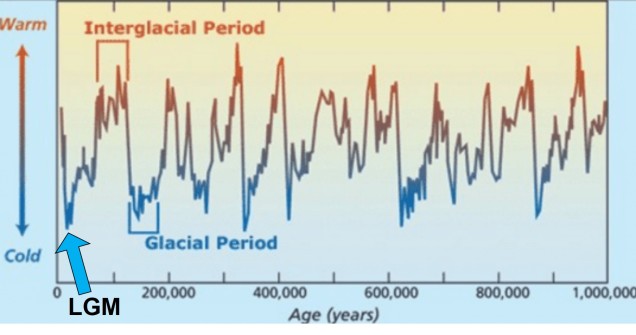

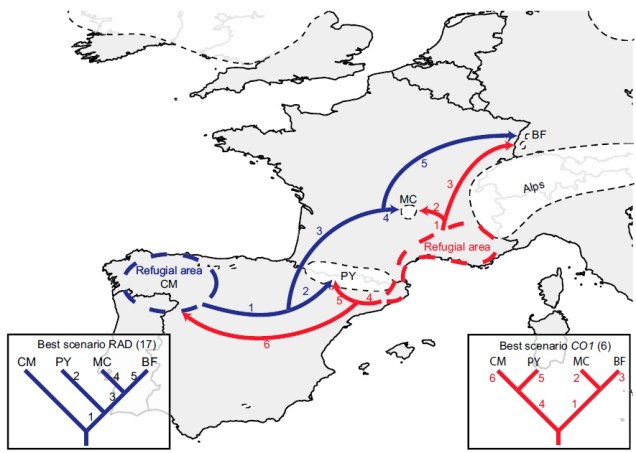

The processes driving genetic differentiation, and the progressive development of populations along the speciation continuum, are complex in nature and influenced by a number of factors. Generally, on The G-CAT we have considered the temporal aspects of these factors: how time much time is needed for genetic differentiation, how this might not be consistent across different populations or taxa, and how a history of environmental changes affect the evolution of populations and species. We’ve also touched on the spatial aspects of speciation and genetic differentiation before, but in significantly less detail.

To expand on this, we’re going to look at a few different models of how the spatial distribution of populations influences their divergence, and particularly how these factor into different processes of speciation.

What comes first, ecological or genetic divergence?

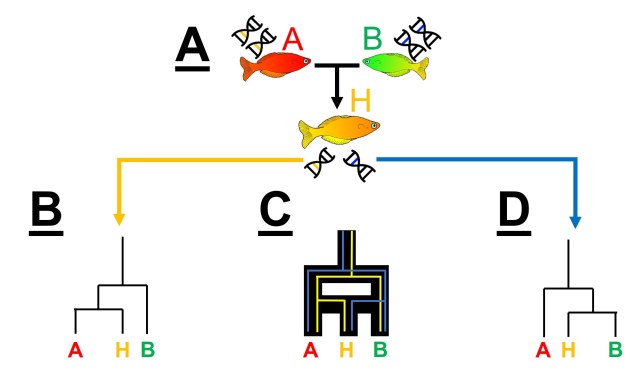

One key paradigm in understanding speciation is somewhat an analogy to the “chicken and the egg scenario”, albeit with ecological vs. genetic divergence. This concept is based on the idea that two aspects are key for determining the formation of new species: genetic differentiation of the populations in question, and ecological (or adaptive) changes that provide new ecological niches for species to inhabit. Without both, we might have new morphotypes or ecotypes of a singular species (in the case of ecological divergence without strong genetic divergence) or cryptic species (genetically distinct but ecologically identical species).

The order of these two processes have been in debate for some time, and different aspects of species and the environment can influence how (or if) these processes occur.

Different spatial models of speciation

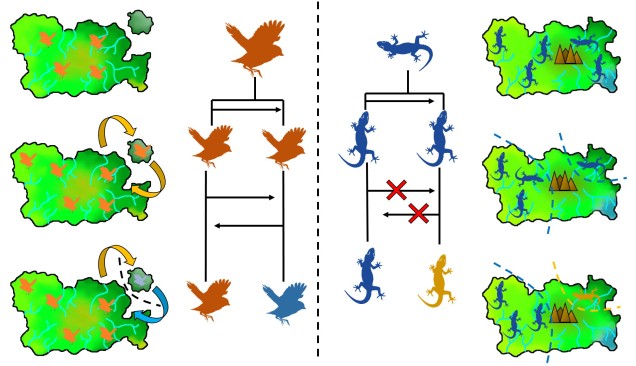

Generally, when we consider the spatial models for speciation we divide these into distinct categories based on the physical distance of populations from one another. Although there is naturally a lot of grey area (as there is with almost everything in biological science), these broad concepts help us to define and determine how speciation is occurring in the wild.

Allopatric speciation

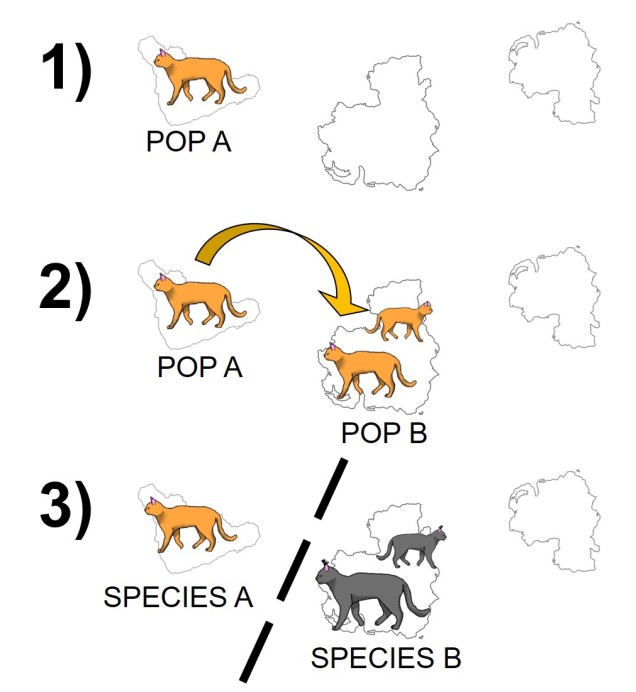

The simplest model is one we have described before called “allopatry”. In allopatry, populations are distributed distantly from one another, so that there are separated and isolated. A common way to imagine this is islands of populations separated by ocean of unsuitable habitat.

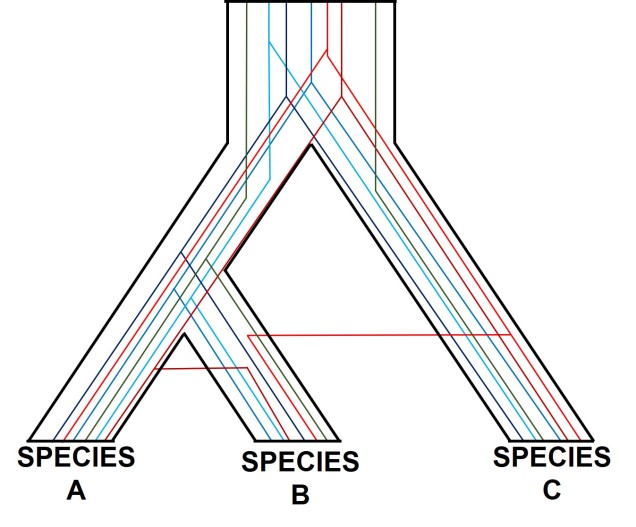

Allopatric speciation is considered one of the simplest and oldest models of speciation as the process is relatively straightforward. Geographic isolation of populations separates them from one another, meaning that gene flow is completely stopped and each population can evolve independently. Small changes in the genes of each population over time (e.g. due to different natural selection pressures) cause these populations to gradually diverge: eventually, this divergence will reach a point where the two populations would not be compatible (i.e. are reproductively isolated) and thus considered separate species.

Although relatively straightforward, one complex issue of allopatric speciation is providing evidence that hybridisation couldn’t happen if they reconnected, or if populations could be considered separate species if they could hybridise, but only under forced conditions (i.e. it is highly unlikely that the two ‘species’ would interact outside of experimental conditions).

Parapatric and peripatric speciation

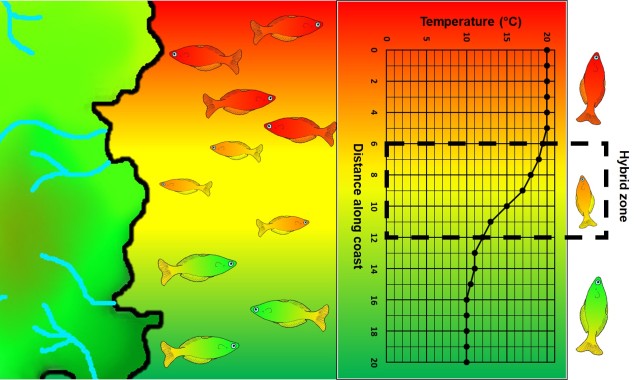

A step closer in bringing populations geographically together in speciation is “parapatry” and “peripatry”. Parapatric populations are often geographically close together but not overlapping: generally, the edges of their distributions are touching but do not overlap one another. A good analogy would be to think of countries that share a common border. Parapatry can occur when a species is distributed across a broad area, but some form of narrow barrier cleaves the distribution in two: this can be the case across particular environmental gradients where two extremes are preferred over the middle.

The main difference between paraptry and allopatry is the allowance of a ‘hybrid zone’. This is the region between the two populations which may not be a complete isolating barrier (unlike the space between allopatric populations). The strength of the barrier (and thus the amount of hybridisation and gene flow across the two populations) is often determined by the strength of the selective pressure (e.g. how unfit hybrids are). Paraptry is expected to reduce the rate and likelihood of speciation occurring as some (even if reduced) gene flow across populations is reduces the amount of genetic differentiation between those populations: however, speciation can still occur.

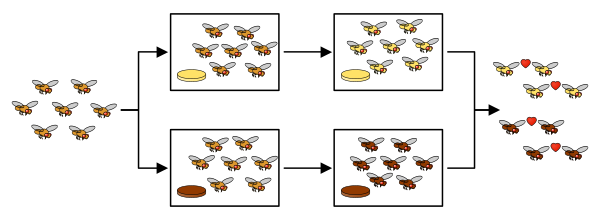

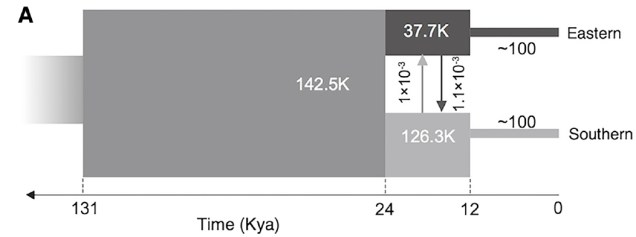

Related to this are peripatric populations. This differs from parapatry only slightly in that one population is an original ‘source’ population and the other is a ‘peripheral’ population. This can happen from a new population becoming founded from the source by a rare dispersal event, generating a new (but isolated) population which may diverge independently of the source. Alternatively, peripatric populations can be formed when the broad, original distribution of the species is reduced during a population contraction, and a remnant piece of the distribution becomes fragmented and ‘left behind’ in the process, isolated from the main body. Speciation can occur following similar processes of allopatric speciation if gene flow is entirely interrupted or paraptric if it is significantly reduced but still present.

Sympatric (ecological) speciation

On the other end of the distribution spectrum, the two diverging populations undergoing speciation may actually have completely overlapping distributions. In this case, we refer to these populations as “sympatric”, and the possibility of sympatric speciation has been a highly debated topic in evolutionary biology for some time. One central argument rears its head against the possibility of sympatric speciation, in that if populations are co-occurring but not yet independent species, then gene flow should (theoretically) occur across the populations and prevent divergence.

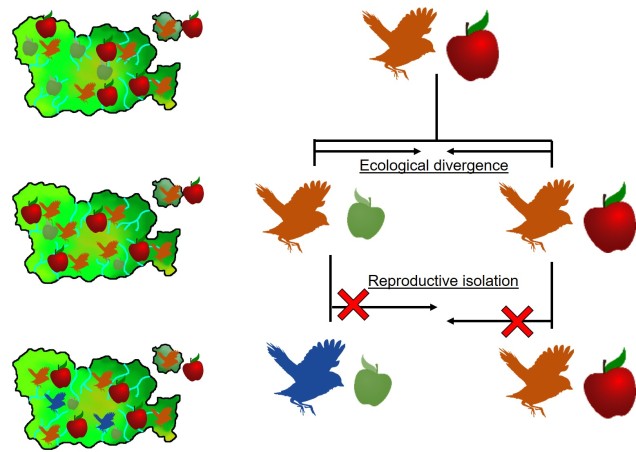

It is in sympatric speciation that we see the opposite order of ecological and genetic divergence happen. Because of this, the process is often referred to as “ecological speciation”, where individual populations adapt to different niches within the same area, isolating themselves from one another by limiting their occurrence and tolerances. As the two populations are restricted from one another by some kind of ecological constraint, they genetically diverge over time and speciation can occur.

This can be tricky to visualise, so let’s invent an example. Say we have a tropical island, which is occupied by one bird species. This bird prefers to eat the large native fruit of the island, although there is another fruit tree which produces smaller fruits. However, there’s only so much space and eventually there are too many birds for the number of large fruit trees available. So, some birds are pushed to eat the smaller fruit, and adapt to a different diet, changing physiology over time to better acquire their new food and obtain nutrients. This shift in ecological niche causes the two populations to become genetically separated as small-fruit-eating-birds interact more with other small-fruit-eating-birds than large-fruit-eating-birds. Over time, these divergences in genetics and ecology causes the two populations to form reproductively isolated species despite occupying the same island.

Although this might sound like a simplified example (and it is, no doubt) of sympatric speciation, it’s a basic summary of how we ended up with so many species of Darwin’s finches (and why they are a great model for the process of evolution by natural selection).

The complexity of speciation

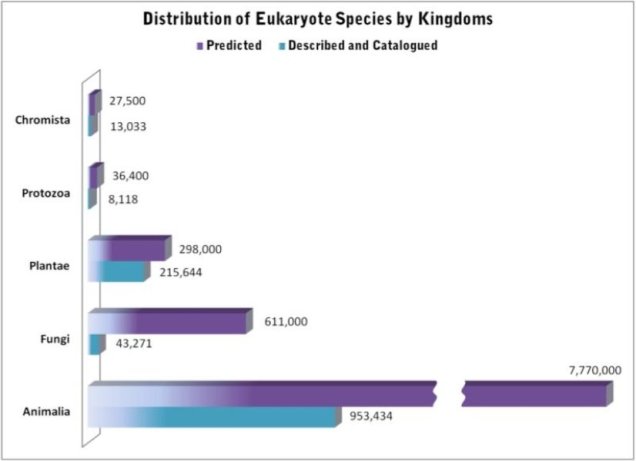

As you can see, the processes and context driving speciation are complex to unravel and many factors play a role in the transition from population to species. Understanding the factors that drive the formation of new species is critical to understanding not just how evolution works, but also in how new diversity is generated and maintained across the globe (and how that might change in the future).