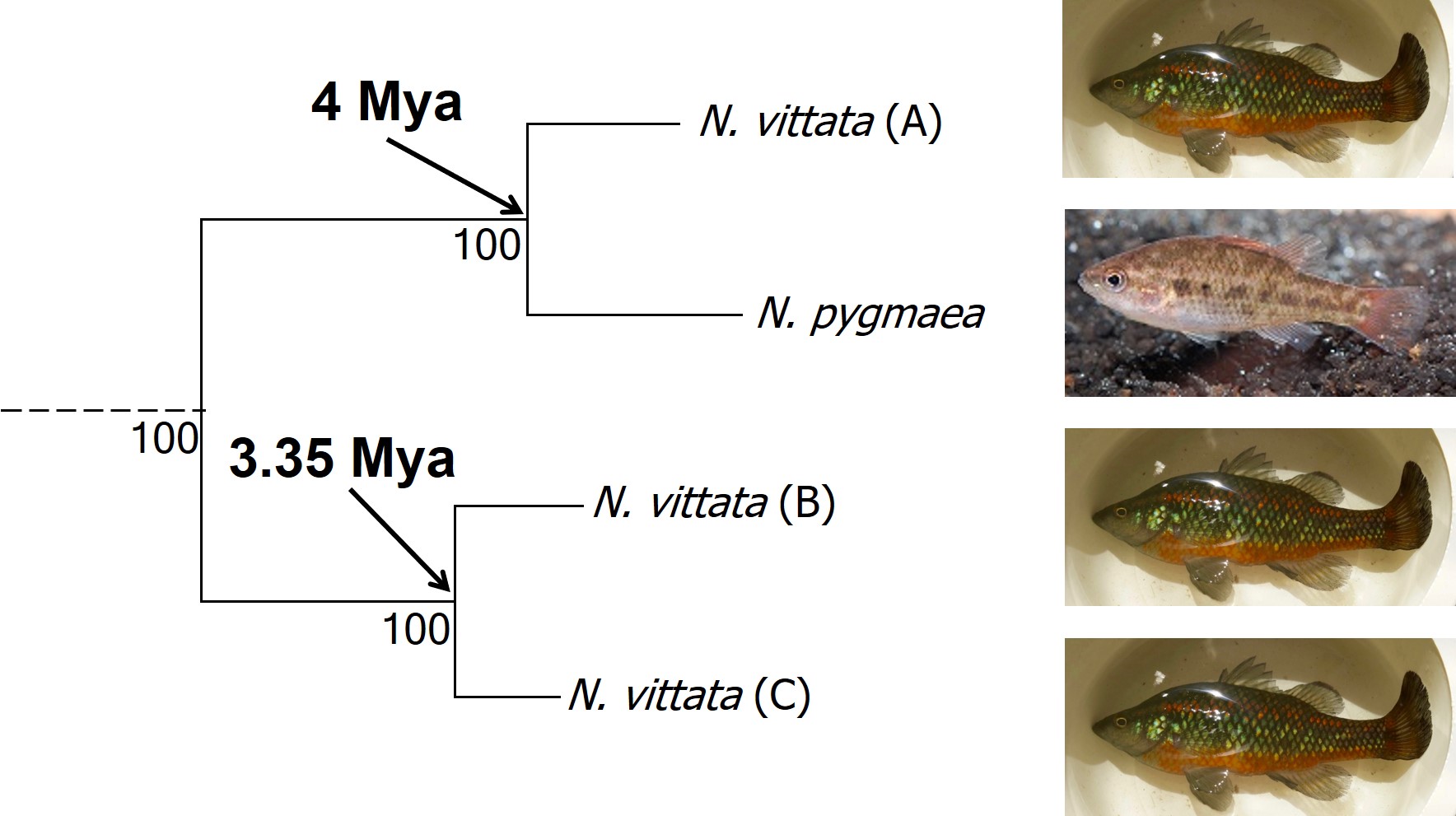

In more fishy news, this week the latest (and last!) chapter of my PhD, describing how millions of years of climatic stability have allowed isolated and divergent lineages of pygmy perches to persist, was published (Open Access) in Heredity. It covers population divergence, phylogenetic relationships (including estimation of divergence times), species delimitation and projections of species distributions from the past (up to three million years ago) into the future (up to 2100). Some highlights include:

Continue readingSpecies delimitation

Dr. G-CAT

Overview of 2020

As you may have gathered, The G-CAT has been significantly less active in this our most Cursed year. There are a number of reasons for that – not just the overall disaster that has been world events – including the fact that this was the last year of my PhD. I’m delighted to announce that now, after ~3.5 years of hard work, I am officially Dr. Buckley (not Dr. G-CAT, as I may have led you to believe)!

Continue readingThe folly of absolute dichotomies

Divide and conquer (nothing)

Divisiveness is becoming quickly apparent as a plague on the modern era. The segregation and categorisation of people – whether politically, spiritually or morally justified – permeates throughout the human condition and in how we process the enormity of the Homo sapien population. The idea that the antithetic extremes form two discrete categories (for example, the waning centrist between ‘left’ vs. ‘right’ political perspectives) is widely employed in many aspects of the world.

But how pervasive is this pattern? How well can we summarise, divide and categorise people? For some things, this would appear innately very easy to do – one of the most commonly evoked divisions in people is that between men and women. But the increasingly charged debate around concepts of both gender and sex (and sexuality as a derivative, somewhat interrelated concept) highlights the inconsistency of this divide.

The ‘sex’ and ‘gender’ arguments

The most commonly used argument against ‘alternative’ concepts of either gender of sex – the binary states of a ‘man’ with a ‘male’ body and a ‘female’ with a ‘female’ body – is often based on some perception of “biologically reality.” As a (trainee) biologist, let me make this apparently clear that such confidence and clarity of “reality” in many, if not all, biological subdisciplines is absurd (e.g. “nature vs. nurture”). Biologists commonly acknowledge (and rely upon) the realisation that life in all of its constructs is unfathomably diverse, unique, and often difficult to categorise. Any impression of being able to do so is a part of the human limitation to process concepts without boundaries.

Gender as a binary

In terms of gender identity, I think this is becoming (slowly) more accepted over time. That most people have a gender identity somewhere along a multidimensional spectrum is not, for many people, a huge logical leap. Trans people are not mentally ill, not all ‘men’ identify as ‘men’ and certainly not all ‘men’ identify as a ‘man’ under the same characteristics or expression. Human psychology is beautifully complex and to reduce people down to the most simplistic categories is, in my humble opinion, a travesty. The single-variable gender binary cannot encapsulate the full depth of any single person’s identity or personality, and this biologically makes sense.

Sex as a binary

As an extension of the gender debate, sex itself has often been relied upon as the last vestige of some kind of sexual binary. Even for those more supported of trans people, sex is often described as some concrete, biologically, genetically-encoded trait which conveniently falls into its own binary system. Thus, instead of a single binary, people are reduced down to a two-character matrix of sex and gender.

However, the genetics of the definition and expression of sex is in itself a complex network of the expression of different genes and the presence of different chromosomes. Although high-school level biology teaches us that men are XY and women are XX genetically, individual genes within those chromosomes can alter the formation of different sexual organs and the development of a person. Furthermore, additional X or Y chromosomes can further alter the way sexual development occurs in people. Many people who fall in between the two ends of the gender spectrum of Male and Female identify as ‘intersex’.

You might be under the impression that these are rare ‘genetic disorders’, and don’t count as “real people” (decidedly not my words). But the reality is that intersex people are relatively common throughout the world, and occur roughly as frequently as true redheads or green eyes. Thus, the idea that excluding intersex people from the rest of societal definitions has very little merit, especially from a scientific point of view. Instead, allowing our definitions of both sex and gender to be broad and flexible allows us to incorporate the biological reality of the immense diversity of the world, even just within our own species.

Absolute species concepts

Speaking of species, and relating this paradigm of dichotomy to potentially less politically charged concepts, species themselves are a natural example on the inaccuracy of absolutism. This idea is not a new one, either within The G-CAT or within the broad literature, and species identity has long been regarded as a hive of grey areas. The sheer number of ways a group of organisms can be divided into species (or not, as the case may be) lends to the idea that simplified definitions of what something is or is not will rarely be as accurate as we hope. Even the most commonly employed of characteristics – such as those of the Biological Species Concept – cannot be applied to a number of biological systems such as asexually-reproducing species or complex cases of isolation.

The diversity of Life

Anyone who argues a biological basis for these concepts is taking the good name of biological science hostage. Diversity underpins the most core aspects of biology (e.g. evolution, communities and ecosystems, medicine) and is a real attribute of living in a complicated world. Downscaling and simplifying the world to the ‘black’ and the ‘white’ discredits the wonder of biology, and acknowledging the ‘outliers’ (especially those that are not actually so far outside the boxes we have drawn) of any trends we may observe in nature is important to understand the complexity of life on Earth. Even if individual components of this post seem debatable to you: always remember that life is infinitely more complex and colourful than we can even imagine, and all of that is underpinned by diversity in one form or another.

An identity crisis: using genomics to determine species identities

This is the fourth (and final) part of the miniseries on the genetics and process of speciation. To start from Part One, click here.

In last week’s post, we looked at how we can use genetic tools to understand and study the process of speciation, and particularly the transition from populations to species along the speciation continuum. Following on from that, the question of “how many species do I have?” can be further examined using genetic data. Sometimes, it’s entirely necessary to look at this question using genetics (and genomics).

Cryptic species

A concept that I’ve mentioned briefly previously is that of ‘cryptic species’. These are species which are identifiable by their large genetic differences, but appear the same based on morphological, behavioural or ecological characteristics. Cryptic species often arise when a single species has become fragmented into several different populations which have been isolated for a long time from another. Although they may diverge genetically, this doesn’t necessarily always translate to changes in their morphology, ecology or behaviour, particularly if these are strongly selected for under similar environmental conditions. Thus, we need to use genetic methods to be able to detect and understand these species, as well as later classify and describe them.

Genetic tools to study species: the ‘Barcode of Life’

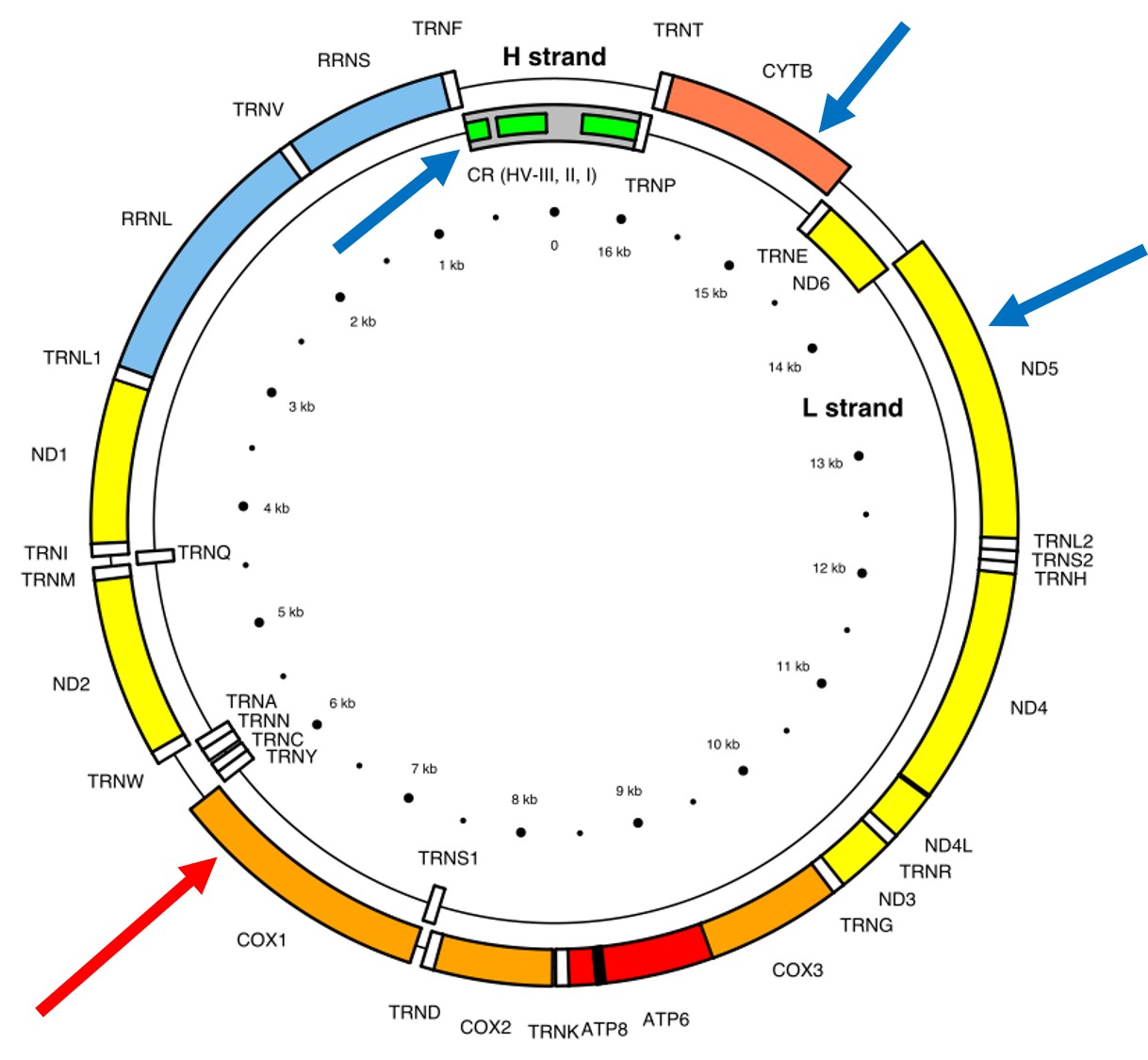

A classically employed method that uses DNA to detect and determine species is referred to as the ‘Barcode of Life’. This uses a very specific fragment of DNA from the mitochondria of the cell: the cytochrome c oxidase I gene, CO1. This gene is made of 648 base pairs and is found pretty well universally: this and the fact that CO1 evolves very slowly make it an ideal candidate for easily testing the identity of new species. Additionally, mitochondrial DNA tends to be a bit more resilient than its nuclear counterpart; thus, small or degraded tissue samples can still be sequenced for CO1, making it amenable to wildlife forensics cases. Generally, two sequences will be considered as belonging to different species if they are certain percentage different from one another.

Despite the apparent benefits of CO1, there are of course a few drawbacks. Most of these revolve around the mitochondrial genome itself. Because mitochondria are passed on from mother to offspring (and not at all from the father), it reflects the genetic history of only one sex of the species. Secondly, the actual cut-off for species using CO1 barcoding is highly contentious and possibly not as universal as previously suggested. Levels of sequence divergence of CO1 between species that have been previously determined to be separate (through other means) have varied from anywhere between 2% to 12%. The actual translation of CO1 sequence divergence and species identity is not all that clear.

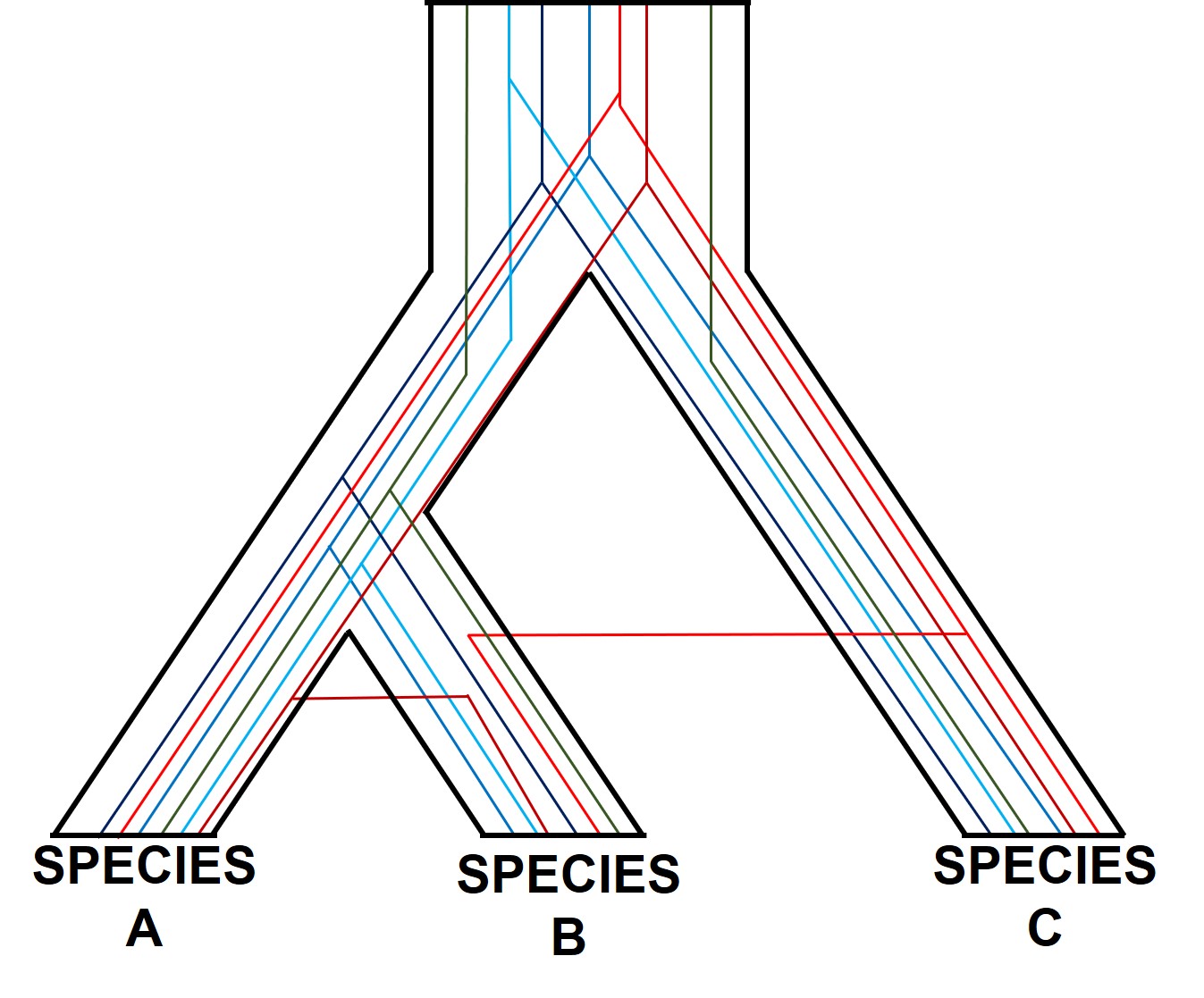

Gene tree – species tree incongruences

One particularly confounding aspect of defining species based on a single gene, and with using phylogenetic-based methods, is that the history of that gene might not actually be reflective of the history of the species. This can be a little confusing to think about but essentially leads to what we call “gene tree – species tree incongruence”. Different evolutionary events cause different effects on the underlying genetic diversity of a species (or group of species): while these may be predictable from the genetic sequence, different parts of the genome might not be as equally affected by the same exact process.

A classic example of this is hybridisation. If we have two initial species, which then hybridise with one another, we expect our resultant hybrids to be approximately made of 50% Species A DNA and 50% Species B DNA (if this is the first generation of hybrids formed; it gets a little more complicated further down the track). This means that, within the DNA sequence of the hybrid, 50% of it will reflect the history of Species A and the other 50% will reflect the history of Species B, which could differ dramatically. If we randomly sample a single gene in the hybrid, we will have no idea if that gene belongs to the genealogy of Species A or Species B, and thus we might make incorrect inferences about the history of the hybrid species.

There are a number of other processes that could similarly alter our interpretations of evolutionary history based on analysing the genetic make-up of the species. The best way to handle this is simply to sample more genes: this way, the effect of variation of evolutionary history in individual genes is likely to be overpowered by the average over the entire gene pool. We interpret this as a set of individual gene trees contained within a species tree: although one gene might vary from another, the overall picture is clearer when considering all genes together.

Species delimitation

In earlier posts on The G-CAT, I’ve discussed the biogeographical patterns unveiled by my Honours research. Another key component of that paper involved using statistical modelling to determine whether cryptic species were present within the pygmy perches. I didn’t exactly elaborate on that in that section (mostly for simplicity), but this type of analysis is referred to as ‘species delimitation’. To try and simplify complicated analyses, species delimitation methods evaluate possible numbers and combinations of species within a particular dataset and provides a statistical value for which configuration of species is most supported. One program that employs species delimitation is Bayesian Phylogenetics and Phylogeography (BPP): to do this, it uses a plethora of information from the genetics of the individuals within the dataset. These include how long ago the different populations/species separated; which populations/species are most related to one another; and a pre-set minimum number of species (BPP will try to combine these in estimations, but not split them due to computational restraints). This all sounds very complex (and to a degree it is), but this allows the program to give you a statistical value for what is a species and what isn’t based on the genetics and statistical modelling.

The end result of a BPP run is usually reported as a species tree (e.g. a phylogenetic tree describing species relationships) and statistical support for the delimitation of species (0-1 for each species). Because of the way the statistical component of BPP works, it has been found to give extremely high support for species identities. This has been criticised as BPP can, at time, provide high statistical support for genetically isolated lineages (i.e. divergent populations) which are not actually species.

Improving species identities with integrative taxonomy

Due to this particular drawback, and the often complex nature of species identity, using solely genetic information such as species delimitation to define species is extremely rare. Instead, we use a combination of different analytical techniques which can include genetic-based evaluations to more robustly assign and describe species. In my own paper example, we suggested that up to three ‘species’ of N. vittata that were determined as cryptic species by BPP could potentially exist pending on further analyses. We did not describe or name any of the species, as this would require a deeper delve into the exact nature and identity of these species.

As genetic data and analytical techniques improve into the future, it seems likely that our ability to detect and determine species boundaries will also improve. However, the additional supported provided by alternative aspects such as ecology, behaviour and morphology will undoubtedly be useful in the progress of taxonomy.