The age-old folly of ‘nature vs. nurture’

It should come as no surprise to any reader of The G-CAT that I’m a firm believer against the false dichotomy (and yes, I really do love that phrase) of “nature versus nurture.” Primarily, this is because the phrase gives the impression of some kind of counteracting balance between intrinsic (i.e. usually genetic) and extrinsic (i.e. usually environmental) factors and how they play a role in behaviour, ecology and evolution. While both are undoubtedly critical for adaptation by natural selection, posing this as a black-and-white split removes the possibility of interactive traits.

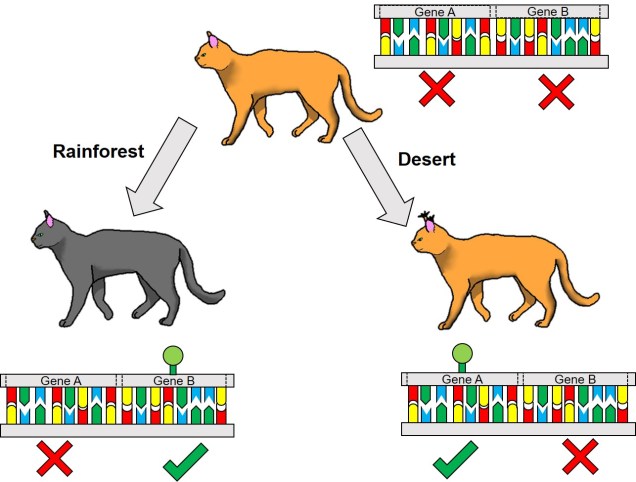

We know readily that fitness, the measure by which adaptation or maladaptation can be quantified, is the product of both the adaptive value of a certain trait and the environmental conditions said trait occurs in. A trait that might confer strong fitness in white environment may be very, very unfit in another. A classic example is fur colour in mammals: in a snowy environment, a white coat provides camouflage for predators and prey alike; in a rainforest environment, it’s like wearing one of those fluoro-coloured safety vests construction workers wear.

Genetically-encoded traits

In the “nature versus nurture” context, the ‘nature’ traits are often inherently assumed to be genetic. This is because genetic traits are intrinsic as a fundamental aspect of life, inheritable (and thus can be passed on and undergo evolution by natural selection) and define the important physiological traits that provide (or prevent) adaptation. Of course, not all of the genome encodes phenotypic traits at all, and even less relate to diagnosable and relevant traits for natural selection to act upon. In addition, there is a bit of an assumption that many physiological or behavioural traits are ‘hardwired’: that is, despite any influence of environment, genes will always produce a certain phenotype.

Despite how important the underlying genes are for the formation of proteins and definition of physiology, they are not omnipotent in that regard. In fact, many other factors can influence how genetic traits relate to phenotypic traits: we’ve discussed a number of these in minor detail previously. An example includes interactions across different genes: these can be due to physiological traits encoded by the cumulative presence and nature of many loci (as in quantitative trait loci and polygenic adaptation). Alternatively, one gene may translate to multiple different physiological characters if it shows pleiotropy.

Differential expression

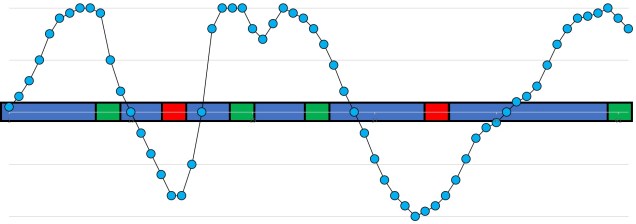

One non-direct way genetic information can impact on the phenotype of an organism is through something we’ve briefly discussed before known as differential expression. This is based on the notion that different environmental pressures may affect the expression (that is, how a gene is translated into a protein) in alternative ways. This is a fundamental underpinning of what we call phenotypic plasticity: the concept that despite having the exact same (or very similar) genes and alleles, two clonal individuals can vary in different traits. The is related to the example of genetically-identical twins which are not necessarily physically identical; this could be due to environmental constraints on growth, behaviour or personality.

From an evolutionary perspective, the ability to translate a single gene into multiple phenotypic traits has a strong advantage. It allows adaptation to new, novel environments without waiting for natural selection to favour adaptive mutations (or for new, adaptive alleles to become available from new mutation events). This might be a fundamental trait that determines which species can become invasive pests, for instance: the ability to establish and thrive in environments very different to their native habitat allows introduced species to quickly proliferate and spread. Even for species which we might not consider ‘invasive’ (i.e. they have naturally spread to new environments), phenotypic plasticity might allow them to very rapidly adapt and evolve into new ecological niches and could even underpin the early stages of the speciation process.

Epigenetics

Related to this alternative expression of genes is another relatively recent concept: that of epigenetics. In epigenetics, the expression and function of genes is controlled by chemical additions to the DNA which can make gene expression easier or more difficult, effectively promoting or silencing genes. Generally, the specific chemicals that are attached to the DNA are relatively (but not always) predictable in their effects: for example, the addition of a methyl group to the sequence is generally associated with the repression of the gene underlying it. How and where these epigenetic markers may in turn be affected by environmental conditions, creating a direct conduit between environmental (‘nurture’) and intrinsic genetic (‘nature’) aspects of evolution.

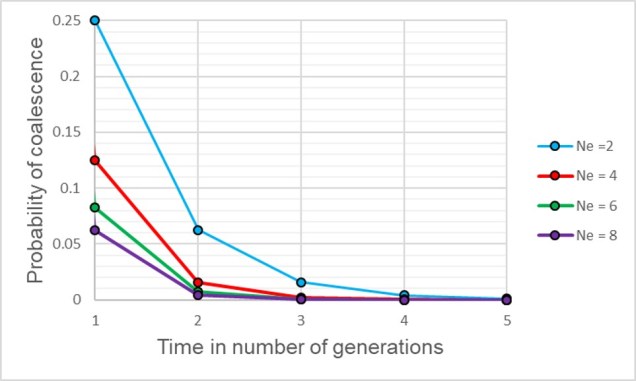

Typically, these epigenetic ‘marks’ (chemical additions to the DNA) are erased and reset during fertilisation: the epigenetic marks on the parental gametes are removed, and new marks are made on the fertilised embryo. However, it has been shown that this removal process is not 100% effective, and in fact some marks are clearly passed down from parent to offspring. This means that these marks are heritable, and could allow them to evolve similarly to full DNA mutations.

The discovery of epigenetic markers and their influence on gene expression has opened up the possibility of understanding heritable traits which don’t appear to be clearly determined by genetics alone. For example, research into epigenetics suggest that heritable major depressive disorder (MDD) may be controlled by the expression of genes, rather than from specific alleles or genetic variants themselves. This is likely true for a number of traits for which the association to genotype is not entirely clear.

Epigenetic adaptation?

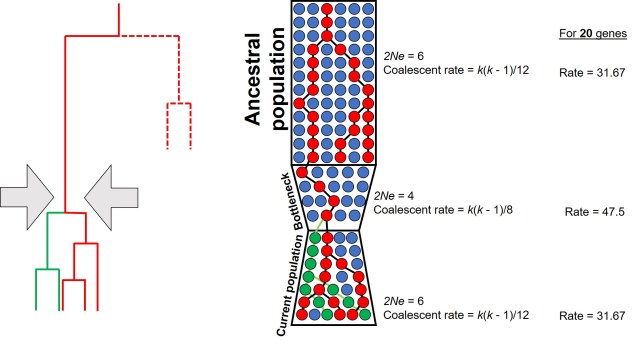

From an evolutionary standpoint again, epigenetics can similarly influence the ‘bang for a buck’ of particular genes. Being able to translate a single gene into many different forms, and for this to be linked to environmental conditions, allows organisms to adapt to a variety of new circumstances without the need for specific adaptive genes to be available. Following this logic, epigenetic variation might be critically important for species with naturally (or unnaturally) low genetic diversity to adapt into the future and survive in an ever-changing world. Thus, epigenetic information might paint a more optimistic outlook for the future: although genetic variation is, without a doubt, one of the most fundamental aspects of adaptability, even horrendously genetically depleted populations and species might still be able to be saved with the right epigenetic diversity.

Epigenetic research, especially from an ecological/evolutionary perspective, is a very new field. Our understanding of how epigenetic factors translate into adaptability, the relative performance of epigenetic vs. genetic diversity in driving adaptability, and how limited heritability plays a role in adaptation is currently limited. As with many avenues of research, further studies in different contexts, experiments and scopes will reveal further this exciting new aspect of evolutionary and conservation genetics. In short: watch this space! And remember, ‘nature is nurture’ (and vice versa)!