What is a ‘model’?

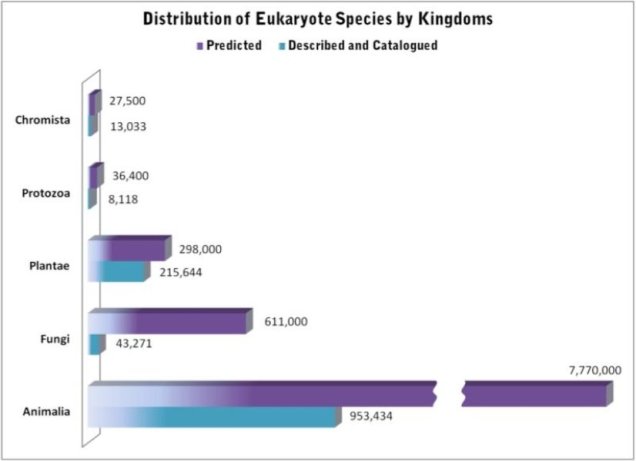

There are quite literally millions of species on Earth, ranging from the smallest of microbes to the largest of mammals. In fact, there are so many that we don’t actually have a good count on the sheer number of species and can only estimate it based on the species we actually know about. Unsurprisingly, then, the number of species vastly outweighs the number of people that research them, especially considering the sheer volumes of different aspects of species, evolution, conservation and their changes we could possibly study.

This is partly where the concept of a ‘model’ comes into it: it’s much easier to pick a particular species to study as a target, and use the information from it to apply to other scenarios. Most people would be familiar with the concept based on medical research: the ‘lab rat’ (or mouse). The common house mouse (Mus musculus) and the brown rat (Rattus norvegicus) are some of the most widely used models for understanding the impact of particular biochemical compounds on physiology and are often used as the testing phase of medical developments before human trials.

So, why are mice used as a ‘model’? What actually constitutes a ‘model’, rather than just a ‘relatively-well-research-species’? Well, there are a number of traits that might make certain species ideal subjects for understanding key concepts in evolution, biology, medicine and ecology. For example, mice are often used in medical research given their (relative) similar genetic, physiological and behavioural characteristics to humans. They’re also relatively short-lived and readily breed, making them ideal to observe the more long-term effects of medical drugs or intergenerational impacts. Other species used as models primarily in medicine include nematodes (Caenorhabditis elegans), pigs (Sus scrofa domesticus), and guinea pigs (Cavia porcellus).

The diversity of models

There are a wide variety and number of different model species, based on the type of research most relevant to them (and how well it can be applied to other species). Even with evolution and conservation-based research, which can often focus on more obscure or cryptic species, there are several key species that have widely been applied as models for our understanding of the evolutionary process. Let’s take a look at a few examples for evolution and conservation.

Drosophila

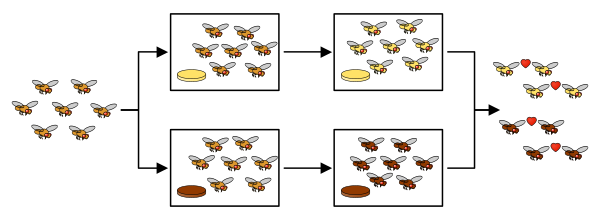

It would be remiss of me to not mention one of the most significant contributors to our understanding of the genetic underpinning of adaptation and speciation, the humble fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster, among other species). The ability to rapidly produce new generations (with large numbers of offspring with very short generation time), small fully-sequenced genome, and physiological variation means that observing both phenotypic and genotypic changes over generations due to ‘natural’ (or ‘experimental’) selection are possible. In fact, Drosphilia spp. were key in demonstrating the formation of a new species under laboratory conditions, providing empirical evidence for the process of natural selection leading to speciation (despite some creationist claims that this has never happened).

Darwin’s finches

The original model of evolution could be argued to be Darwin’s finches, as the formed part of the empirical basis of Charles Darwin’s work on the theory of evolution by natural selection. This is because the different species demonstrate very distinct and obvious changes in morphology related to a particular diet (e.g. the physiological consequences of natural selection), spread across an archipelago in a clear demonstration of a natural experiment. Thus, they remain the original example of adaptive radiation and are fundamental components of the theory of evolution by natural selection. However, surprisingly, Darwin’s finches are somewhat overshadowed in modern research by other species in terms of the amount of available data.

Zebra finches

Even as far as birds go, one species clearly outshines the rest in terms of research. The zebra finch is one of the most highly researched vertebrate species, particularly as a model of song learning and behaviour in birds but also as a genetic model. The full genome of the zebra finch was the second bird to ever be sequenced (the first being a chicken), and remains one of the more detailed and annotated genomes in birds. Because of this, the zebra finch genome is often used as a reference for other studies on the genetics of bird species, especially when trying to understand the function of genetic changes or genes under selection.

Fishes

Fish are (perhaps surprisingly) also relatively well research in terms of evolutionary studies, largely due to their ancient origins and highly diverse nature, with many different species across the globe. They also often demonstrate very rapid and strong bouts of divergence, such as the cichlid fish species of African lakes which demonstrate how new species can rapidly form when introduced to new and variable environments. The cichlids have become the poster child of adaptive radiation in fishes much in the same way that Darwin’s finches highlighted this trend in birds. Another group of fish species used as a model for similar aspects of speciation, adaptive divergence and rapid evolutionary change are the three-spine and nine-spine stickleback species, which inhabit a variety of marine, estuarine and freshwater environments. Thus, studies on the genetic changes across these different morphotypes is a key in understanding how adaptation to new environments occur in nature (particularly the relatively common transition into different water types in fishes).

Zebra fish

More similar to the medical context of lab rats is the zebrafish (ironically, zebra themselves are not considered a model species). Zebrafish are often used as models for understanding embryology and the development of the body in early formation given the rapid speed at which embryonic development occurs and the transparent body of embryos (which makes it easier to detect morphological changes during embryogenesis).

Using information from model species for non-models

While the relevance of information collected from model species to other non-model species depends on the similarity in traits of the two species, our understanding of broad concepts such as evolutionary process, biochemical pathways and physiological developments have significantly improved due to model species. Applying theories and concepts from better understood organisms to less researched ones allows us to produce better research much faster by cutting out some of the initial investigative work on the underlying processes. Thus, model species remain fundamental to medical advancement and evolutionary theory.

That said, in an ideal world all species would have the same level of research and resources as our model species. In this sense, we must continue to strive to understand and research the diversity of life on Earth, to better understand the world in which we live. Full genomes are progressively being sequenced for more and more species, and there are a number of excellent projects that are aiming to sequence at least one genome for all species of different taxonomic groups (e.g. birds, bats, fish). As the data improves for our non-model species, our understanding of evolution, conservation management and medical research will similarly improve.