A tale as old as time

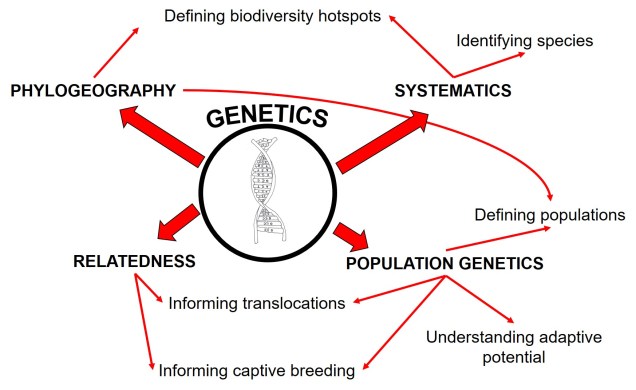

Since evolution is a constant process, occurring over both temporal and spatial scales, the impact of evolutionary history for current and future species cannot be overstated. The various forces of evolution through natural selection have strong, lasting impacts on the evolution of organisms, which is exemplified within the genetic make-up of all species. Phylogeography is the domain of research which intrinsically links this genetic information to historical selective environment (and changes) to understand historic distributions, evolutionary history, and even identify biodiversity hotspots.

The Ice Age(s)

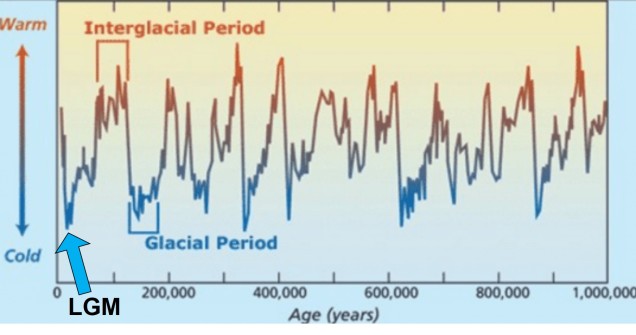

Although there are a huge number of both historic and contemporary climatic factors that have influenced the evolution of species, one particularly important time period is referred to as the Pleistocene glacial cycles. The Pleistocene epoch spans from ~2 million years ago until ~100,000 years ago, and is a time of significant changes in the evolution of many species still around today (particularly for vertebrates). This is because the Pleistocene largely consisted of several successive glacial periods: at times, the climate was significantly cooler, glaciers were more widespread and sea-levels were lower (due to the deeper freezing of water around the poles). These periods were then followed by ‘interglacial periods’, where much of the globe warmed, ice caps melted and sea-levels rose. Sometimes, this natural pattern is argued as explaining 100% of recent climate change: don’t be fooled, however, as Pleistocene cycles were never as dramatic or irreversible as modern, anthropogenically-driven climate change.

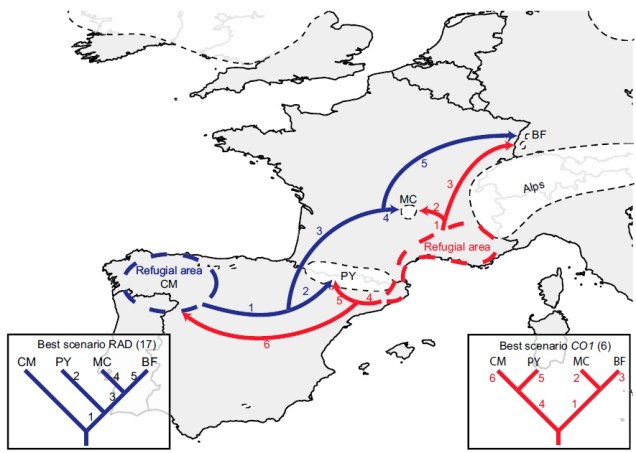

The glacial cycles of the Pleistocene had a number of impacts on a plethora of species on Earth. For many of these species, these glacial-interglacial periods resulted in what we call ‘glacial refugia’ and ‘interglacial expansion’: at the peak of glacial periods, many species’ distributions contracted to small patches of suitable habitat, like tiny islands in a freezing ocean. As the globe warmed during interglacial periods, these habitats started to spread and with them the inhabiting species. While it’s expected that this likely happened many times throughout the Pleistocene, the most clearly observed cycle would be the most recent one: referred to as the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), at ~21,000 years ago. Thus, a quick dive into the literature shows that it is rife with phylogeographic examples of expansions and contractions related to the LGM.

The glacial impact on genetic diversity

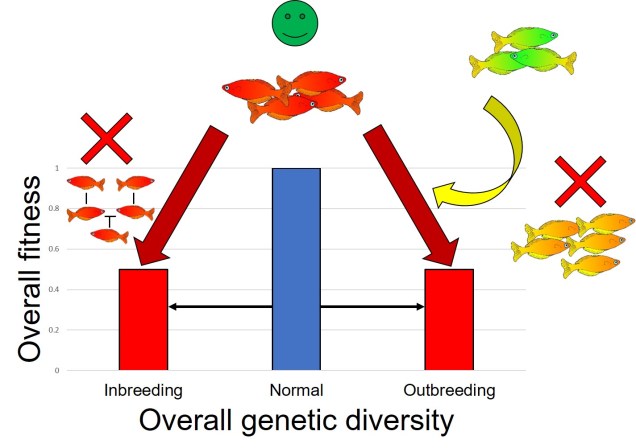

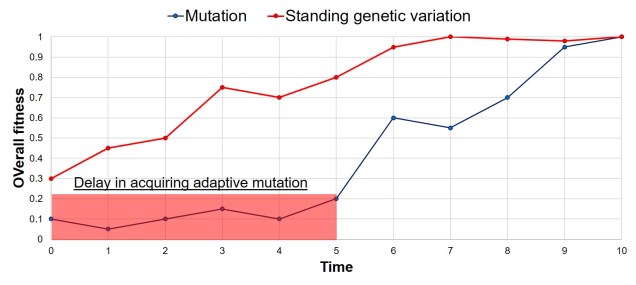

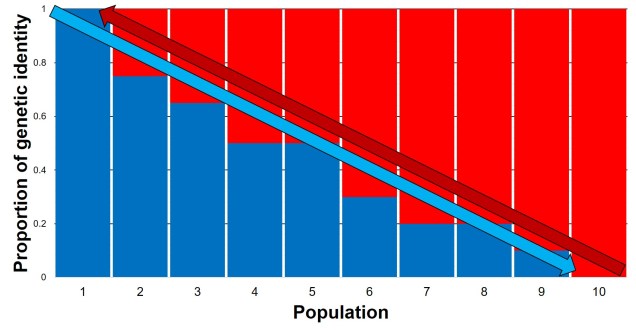

Why does any of this matter? Didn’t it all happen in the past? Well, that leads us back to the original point in this post: forces of evolution leave distinct impacts on the genetic architecture of species. In regards to glacial refugia, a clear pattern is often observed: populations occurring approximately in line with the refugia have maintained greater genetic diversity over time, whilst those in more unstable or unsuitable regions show much more reduced genetic diversity. And this makes sense: many of those populations likely went extinct during glaciation, and only within the last 20,000 or so years have been recolonised from nearby refugia. Accounting for genetic drift due to founder effect, it’s easy to see how this would cause genetic diversity to plummet.

Case study: the charismatic cheetah

And this loss of genetic diversity isn’t just a hypothetical, or an interesting note in evolution. It can have dire impacts for the survivability of species. Take for example, the very charismatic cheetah. Like many large, apex predator species, the cheetah in the modern day is endangered and at risk of extinction to a variety of threats, and although many of these are linked to modern activity (such as being killed to protect farms or habitat clearing), some of these go back much further in history.

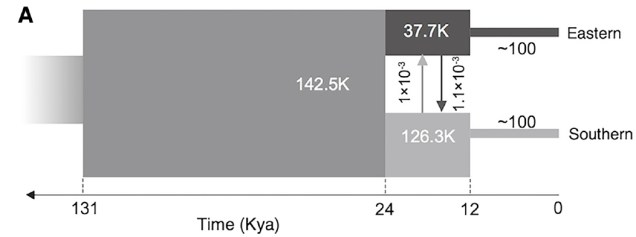

Believe it not, the cheetah as a species actually originated from an ancestor in the Americas: they’re closely related to other American big cats such as the puma/cougar. During the Miocene (5 – 8 million years ago), however, the ancestor of the modern cheetah migrated a very long way to Africa, diverging from its shared ancestor with jaguarandi and cougars. Subsequent migrations into Africa and Asia (where only the Iranian subspecies remains) during the Pleistocene, dated at ~100,000 and ~12,000 years ago, have been shown through whole genome analysis to have resulted in significant reductions in the genetic diversity of the cheetah. This timing correlates with the extinction of the cheetah and puma within North America, and the worldwide extinction of many large mammals including mammoths, dire wolves and sabre-tooth tigers.

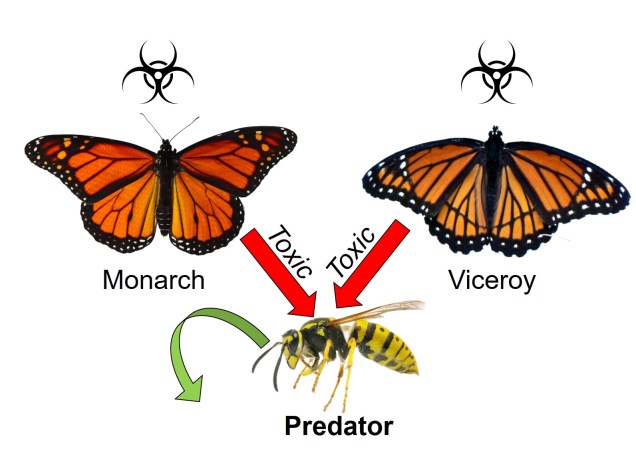

What does this mean for the cheetah? Well, the cheetah has one of the lowest amounts of genetic variation for any living mammal. It’s even lower than the Tasmanian Devil, a species with such notoriously low genetic diversity that a rampant face cancer (Devil Facial Tumour Disease) is transmissible simply because their immune system can’t recognise the transferred cancer cells as being different to the host animal. Similarly, for the cheetah, it’s possible to do reciprocal skin transplants without the likelihood of organ rejection simply because their immune system is incapable of determining the difference between foreign and host tissue cells.

Inference for the future

Understanding the impact of the historic environment on the evolution and genetic diversity of living species is not just important for understanding how species became what they are today. It also helps us understand how species might change in the future, by providing the natural experimental evidence of evolution in a changing climate.