The transition from genotype to phenotype

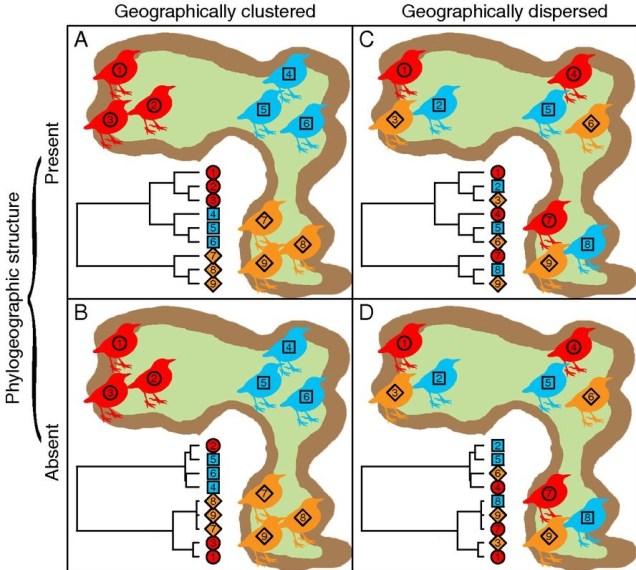

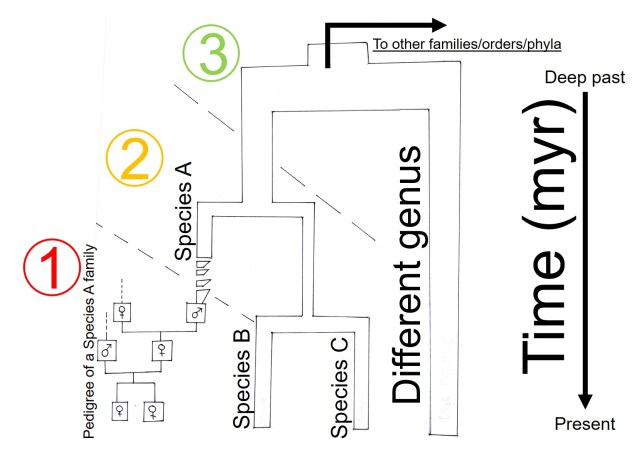

While evolutionary genetics studies often focus on the underlying genetic architecture of species and populations to understand their evolution, we know that natural selection acts directly on physical characteristics. We call these the phenotype; by studying changes in the genes that determine these traits (the genotype), we can take a nuanced approach at studying adaptation. However, our ability to look at genetic changes and relate these to a clear phenotypic trait, and how and why that trait is under natural selection, can be a difficult task.

One gene for one trait

The simplest (and most widely used) models of understanding the genetic basis of adaptation assume that a single genotype codes for a single phenotypic trait. This means that changes in a single gene (such as outliers that we have identified in our analyses) create changes in a particular physical trait that is under a selective pressure in the environment. This is a useful model because it is statistically tractable to be able to identify few specific genes of very large effect within our genomic datasets and directly relate these to a trait: adding more complexity exponentially increases the difficulty in detecting patterns (at both the genotypic and phenotypic level).

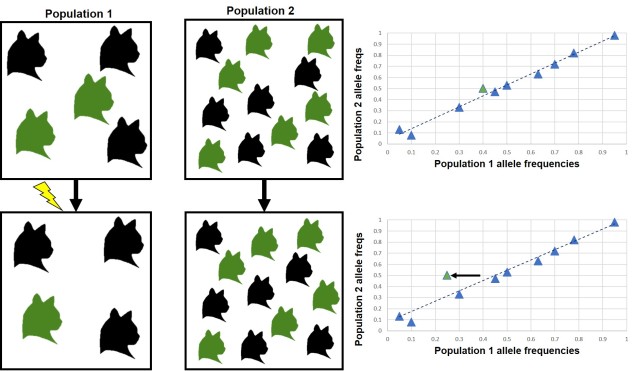

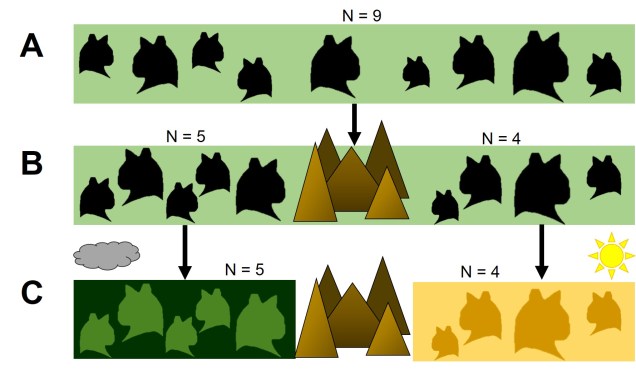

Many genes for one trait: polygenic adaptation

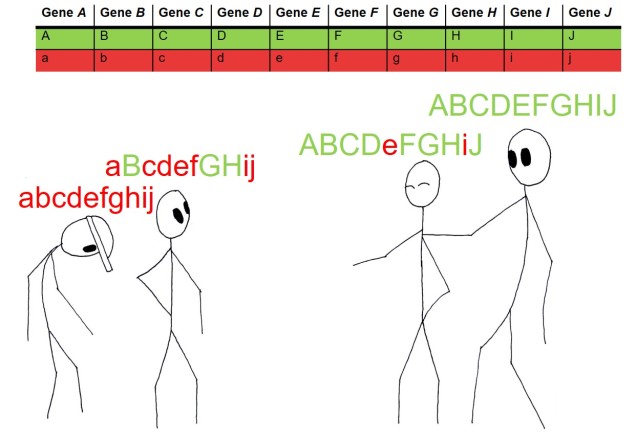

Unfortunately, nature is not always convenient and recent findings suggest that the overwhelming majority of the genetics of adaptation operate under what is called ‘polygenic adaptation’. As the name suggestions, under this scenario changes (even very small ones) in many different genes combine together to have a large effect on a particular phenotypic trait. Given the often very small magnitude of the genetic changes, it can be extremely difficult to separate adaptive changes in genes from neutral changes due to genetic drift. Likewise, trying to understand how these different genes all combine into a single functional trait is almost impossible, especially for non-model species.

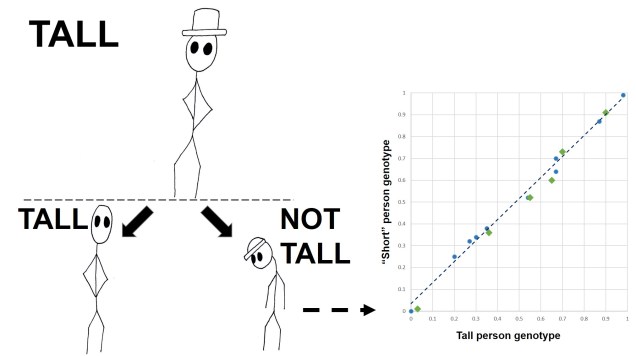

Polygenic adaptation is often seen for traits which are clearly heritable, but don’t show a single underlying gene responsible. Previously, we’ve covered this with the heritability of height: this is one of many examples of ‘quantitative trait loci’ (QTLs). Changes in one QTL (a single gene) causes a small quantitative change in a particular trait; the combined effect of different QTLs together can ‘add up’ (or counteract one another) to result in the final phenotype value.

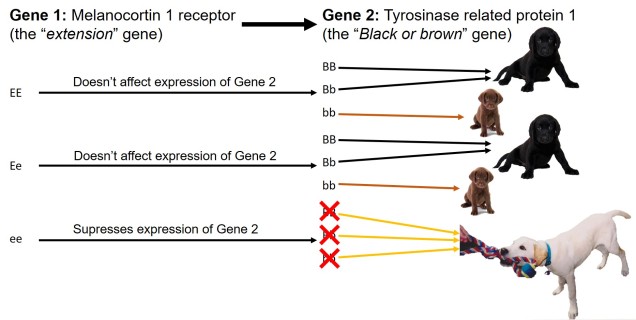

The mechanisms which underlie polygenic adaptation can be more complex than simple addition, too. Individual genes might cause phenotypic changes which interact with other phenotypes (and their underlying genotypes) to create a network of changes. We call these interactions ‘epistasis’, where changes in one gene can cause a flow-on effect of changes in other genes based on how their resultant phenotypes interact. We can see this in metabolic pathways: given that a series of proteins are often used in succession within pathways, a change in any single protein in the process could affect every other protein in the pathway. Of course, knowing the exact proteins coded for every gene, including their physical structure, and how each of those proteins could interact with other proteins is an immense task. Similar to QTLs, this is usually limited to model species which have a large history of research on these specific areas to back up the study. However, some molecular ecology studies are starting to dive into this area by identifying pathways that are under selection instead of individual genes, to give a broader picture of the overall traits that are underlying adaptation.

One gene for many traits: pleiotropy and differential gene expression

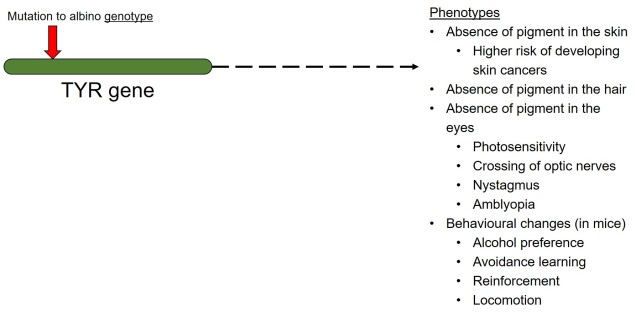

In contrast to polygenic traits, changes in a single gene can also potentially alter multiple phenotypic traits simultaneously. This is referred to as ‘pleiotropy’ and can happen if a gene has multiple different functions within an organism; one particular protein might be a component of several different systems depending on where it is found or how it is arranged. A clear example of pleiotropy is in albino animals: the most common form of albinism is the result of possessing two recessive alleles of a single gene (TYR). The result of this is the absence of the enzyme tyrosinase in the organism, a critical component in the production of melanin. The flow-on phenotypic effects from the recessive gene most obviously cause a lack of pigmentation of the skin (whitening) and eyes (which appear pink), but also other physiological changes such as light sensitivity or total blindness (due to changes in the iris). Albinism has even been attributed to behavioural changes in wild field mice.

Because pleiotropic genes code for several different phenotypic traits, natural selection can be a little more complicated. If some resultant traits are selected against, but others are selected for, it can be difficult for evolution to ‘resolve’ the balance between the two. The overall fitness of the gene is thus dependent on the balance of positive and negative fitness of the different traits, which will determine whether the gene is positively or negatively selected (much like a cost-benefit scenario). Alternatively, some traits which are selectively neutral (i.e. don’t directly provide fitness benefits) may be indirectly selected for if another phenotype of the same underlying gene is selected for.

Multiple phenotypes from a single ‘gene’ can also arise by alternate splicing: when a gene is transcribed from the DNA sequence into the protein, the non-coding intron sections within the gene are removed. However, exactly which introns are removed and how the different coding exons are arranged in the final protein sequence can give rise to multiple different protein structures, each with potentially different functions. Thus, a single overarching gene can lead to many different functional proteins. The role of alternate splicing in adaptation and evolution is a rarely explored area of research and its importance is relatively unknown.

Non-genes for traits: epigenetics

This gets more complicated if we consider ‘non-genetic’ aspects underlying the phenotype in what we call ‘epigenetics’. The phrase literally translates as ‘on top of genes’ and refers to chemical attachments to the DNA which control the expression of genes by allowing or resisting the transcription process. Epigenetics is a relatively new area of research, although studies have started to delve into the role of epigenetic changes in facilitating adaptation and evolution. Although epigenetics is still a relatively new research topic, future research into the relationship between epigenetic changes and adaptive potential might provide more detailed insight into how adaptation occurs in the wild (and might provide a mechanism for adaptation for species with low genetic diversity)!

The different interactions between genotypes, phenotypes and fitness, as well as their complex potential outcomes, inevitably complicates any study of evolution. However, these are important aspects of the adaptation process and to discard them as irrelevant will not doubt reduce our ability to examine and determine evolutionary processes in the wild.