The constancy of evolution

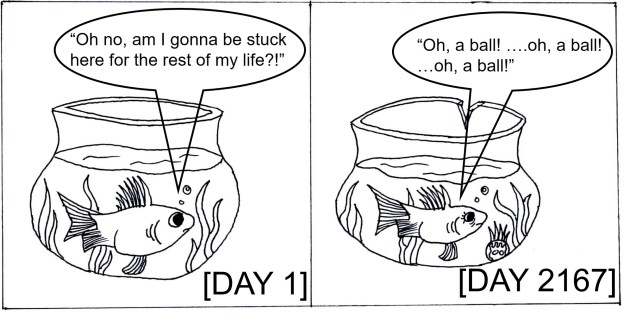

Evolution is a constant, endless force which seeks to push and shape species based on the context of their environment: sometimes rapidly, sometimes much more gradually. Although we often think of discrete points of evolution (when one species becomes two, when a particular trait evolves), it is nevertheless a continual force that influences changes in species. These changes are often difficult to ‘unevolve’ and have a certain ‘evolutionary inertia’ to them; because of these factors, it’s often critical to understand how a history of evolution has generated the organisms we see today.

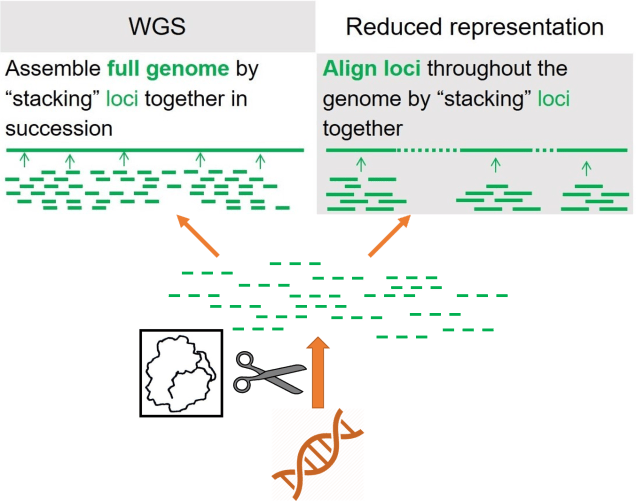

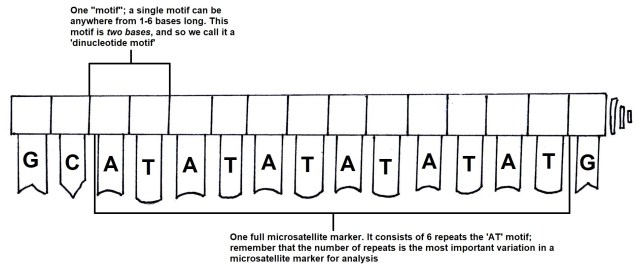

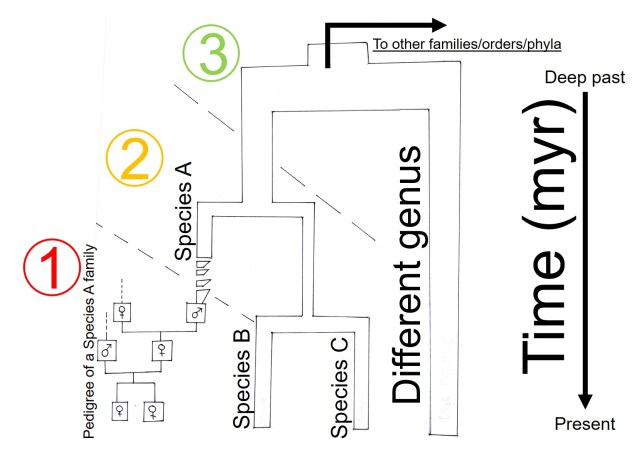

What do I mean when I say evolutionary history? Well, the term is fairly diverse and can relate to the evolution of particular traits or types of traits, or the genetic variation and changes related to these changes. The types of questions and points of interest of evolutionary history can depend at which end of the timescale we look at: recent evolutionary histories, and the genetics related to them, will tell us different information to very ancient evolutionary histories. Let’s hop into our symbolic DeLorean and take a look back in time, shall we?

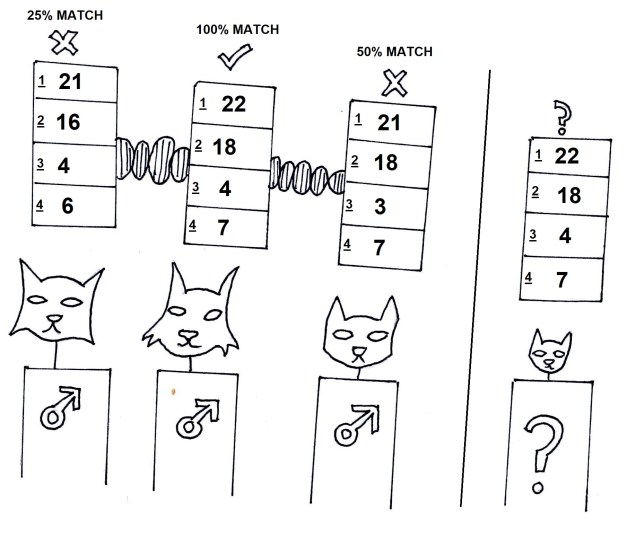

Very recent evolutionary history: pedigrees and populations

While we might ordinarily consider ‘evolutionary history’ to refer to events that happened thousands or millions of years ago, it can still be informative to look at history just a few generations ago. This often involves looking at pedigrees, such as in breeding programs, and trying to see how very short term and rapid evolution may have occurred; this can even include investigating how a particular breeding program might accidentally be causing the species to evolve to adapt to captivity! Rarely does this get referred to as true evolutionary history, but it fits on the spectrum, so I’m going to count it. We might also look at how current populations are evolving differently to one another, to try and predict how they’ll evolve into the future (and thus determine which ones are most at risk, which ones have critically important genetic diversity, and the overall survivability of the total species). This is the basis of ‘evolutionarily significant units’ or ESUs which we previously discussed on The G-CAT.

A little further back: phylogeography and species

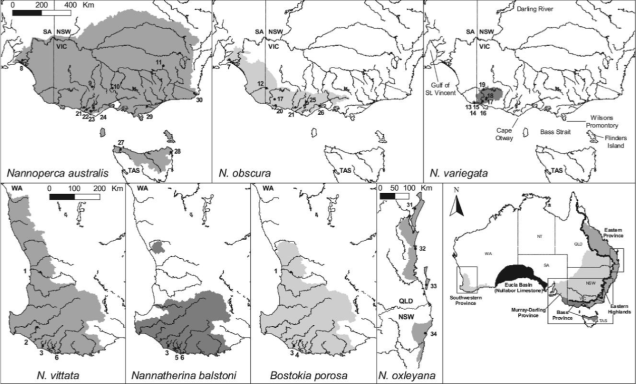

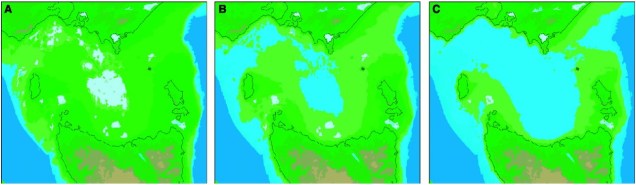

A little further back, we might start to look at how different populations have formed or changed in semi-recent history (usually looking at the effect of human impacts: we’re really good at screwing things up I’m sorry to say). This can include looking at how populations have (or have not) adapted to new pressures, how stable populations have been over time, or whether new populations are being ‘made’ by recent barriers. At this level of populations and some (or incipient) species, we can find the field of ‘phylogeography’, which involves the study of how historic climate and geography have shaped the evolution of species or caused new species to evolve.

One high profile example of phylogeographic studies is the ‘Out of Africa’ hypothesis and debate for the origination of the modern human species. Although there has been no shortage of debate about the origin of modern humans, as well as the fate of our fellow Neanderthals and Denisovans, the ‘Out of Africa’ hypothesis still appears to be the most supported scenario.

Phylogeography is also component for determining and understanding ‘biodiversity hotspots’; that is, regions which have generated high levels of species diversity and contain many endemic species and populations, such as tropical hotspots or remote temperate regions. These are naturally of very high conservation value and contribute a huge amount to Earth’s biodiversity, ecological functions and potential for us to study evolution in action.

Deep, deep history: phylogenetics and the origin of species (groups)

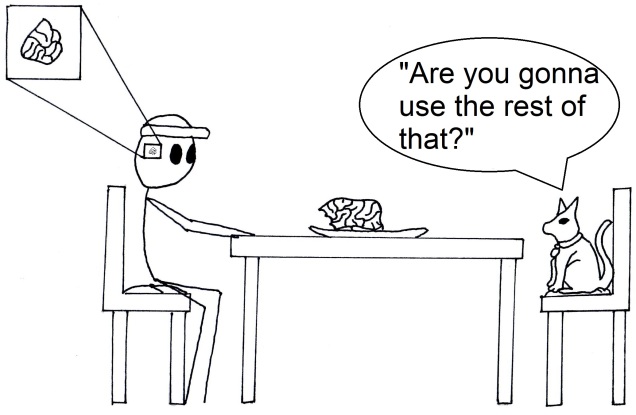

Even further back, we start to delve into the more traditional concept of evolutionary history. We start to look at how species have formed; what factors caused them to become new species, how stable the new species are, and what are the genetic components underlying the change. This subfield of evolution is called ‘phylogenetics’, and relates to understanding how species or groups of species have evolved and are related to one another.

Sometimes, this includes trying to look at how particular diagnostic traits have evolved in a certain group, like venom within snakes or eusocial groups in bees. Phylogenetic methods are even used to try and predict which species of plants might create compounds which are medically valuable (like aspirin)! Similarly, we can try and predict how invasive a pest species may be based on their phylogenetic (how closely related the species are) and physiological traits in order to safeguard against groups of organisms that are likely to run rampant in new environments. It’s important to understand how and why these traits have evolved to get a good understanding of exactly how the diversity of life on Earth came about.

Phylogenetics also allows us to determine which species are the most ‘evolutionarily unique’; all the special little creatures of plant Earth which represent their own unique types of species, such as the tuatara or the platypus. Naturally, understanding exactly how precious and unique these species are suggests we should focus our conservation attention and particularly conserve them, since there’s nothing else in the world that even comes close!

Who cares what happened in the past right? Well, I do, and you should too! Evolution forms an important component of any conservation management plan, since we obviously want to make sure our species can survive into the future (i.e. adapt to new stressors). Trying to maintain the most ‘evolvable’ groups, particularly within breeding programs, can often be difficult when we have to balance inbreeding depression (not having enough genetic diversity) with outbreeding depression (obscuring good genetic diversity by adding bad genetic diversity into the gene pool). Often, we can best avoid these by identifying which populations are evolutionarily different to one another (see ESUs) and using that as a basis, since outbreeding vs. inbreeding depression can be very difficult to measure. This all goes back to the concept of ‘adaptive potential’ that we’ve discussed a few times before.

In any case, a keen understanding of the evolutionary trajectory of a species is a crucial component for conservation management and to figure out the processes and outcomes of evolution in the real world. Thus, evolutionary history remains a key area of research for both conservation and evolution-related studies.