Conservation genetics

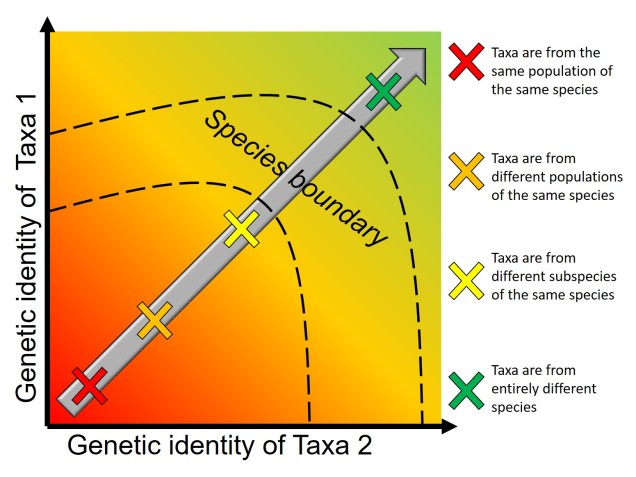

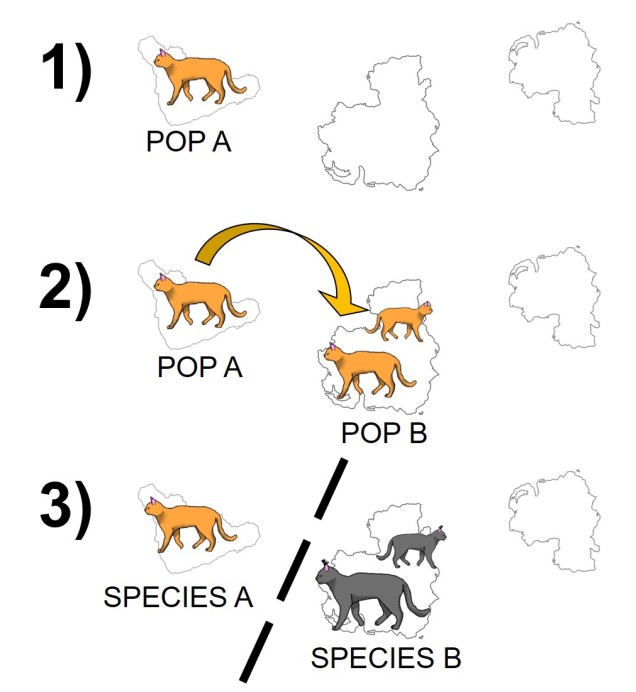

Naturally, all species play their role in the balancing and functioning of ecosystems across the globe (even the ones we might not like all that much, personally). Persistence or extinction of ecologically important species is a critical component of the overall health and stability of an ecosystem, and thus our aim as conservation scientists is to attempt to use whatever tools we have at our disposal to conserve species. One of the most central themes in conservation ecology (and to The G-CAT, of course) is the notion that genetic information can be used to better our conservation management approaches. This usually involves understanding the genetic history and identity of our target threatened species from which we can best plan for their future. This can take the form of genetic-informed relatedness estimates for breeding programs; identifying important populations and those at risk of local extinction; or identifying evolutionarily-important new species which might hold unique adaptations that could allow them to persist in an ever-changing future.

The Invaders

Contrastingly, sometimes we might also use genetic information to do the exact opposite. While so many species on Earth are at risk (or have already passed over the precipice) of extinction, some have gone rogue with our intervention. These are, of course, invasive species; pests that have been introduced into new environments and, by their prolific nature, start to throw out the balance of the ecosystem. Australians will be familiar with no shortage of relevant invasive species; the most notable of which is the cane toad, Rhinella marina. However, there are a plethora of invasive species which range from notably prolific (such as the cane toad) to the seemingly mundane (such as the blackbird): so how can we possibly deal with the number and propensity of pests?

Tools for invasive species management

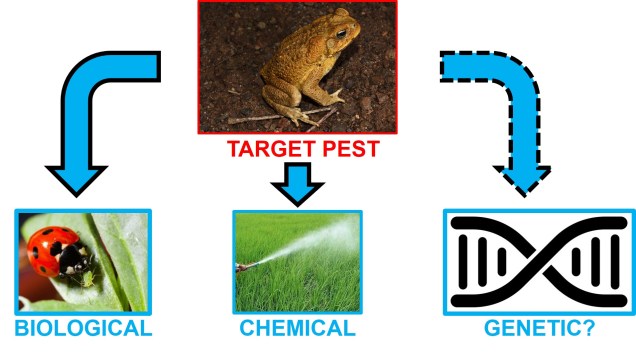

There are a number of tools at our disposal for dealing with invasive species. These range from chemical controls (like pesticides), to biological controls and more recently to targeted genetic methods. Let’s take a quick foray into some of these different methods and their applications to pest control.

Biological controls

One of the most traditional methods of pest control are biological controls. A biological control is, in simple terms, a species that can be introduced to an afflicted area to control the population of an invasive species. Usually, this is based on some form of natural co-evolution or hierarchy: species which naturally predate upon, infect or otherwise displace the pest in question are preferred. The basis of this choice is that nature, and evolution by natural selection, often creates a near-perfect machine adapted for handling the exact problem.

Biological controls can have very mixed results. In some cases, they can be relatively effective, such as the introduction of the moth Cactoblastis cactorum into Australia to control the invasive prickly pear. The moth lays eggs exclusively within the tissue of the prickly pear, and the resultant caterpillars ravish the plant. There has been no association of secondary diet items for caterpillars, suggesting the control method has been very selective and precise.

On the contrary, bad biological controls can lead to ecological disasters. As mentioned above, the introduction of the cane toad into Australia has been widely regarded as the origin of one of the worst invasive pests in the nation’s history. Initially, cane toads were brought over in the 1930s to predate on the (native) cane beetle, which was causing significant damage to sugar cane plantations in the tropical north. Not overly effective at actually dealing with the problem they were supposed to deal with, the cane toad rapidly spread across northern portion of the continent. Native species that attempt to predate on the cane toad often die to their defensive toxin, causing massive ecological damage to the system.

The potential secondary impact of biological controls, and the degree of unpredictability in how they will respond to a new environment (and how native species will also respond to their introduction) leads conservationists to develop new, more specific techniques. In similar ways, viral and bacterial-based controls have had limited success (although are still often proposed in conservation management, such as the planned carp herpesvirus release).

Genetic controls?

It is clear that more targeted and narrow techniques are required to effectively control pest species. At a more micro level, individual genes could be used to manage species: this is not the first way genetic modification has been proposed to deal with problem organisms. Genetic methods have been employed for years in crop farming through genetic engineering of genes to produce ‘natural’ pesticides or insecticides. In a similar vein, it has been proposed that genetic modification could be a useful tool for dealing with invasive pests and their native victims.

Gene drives

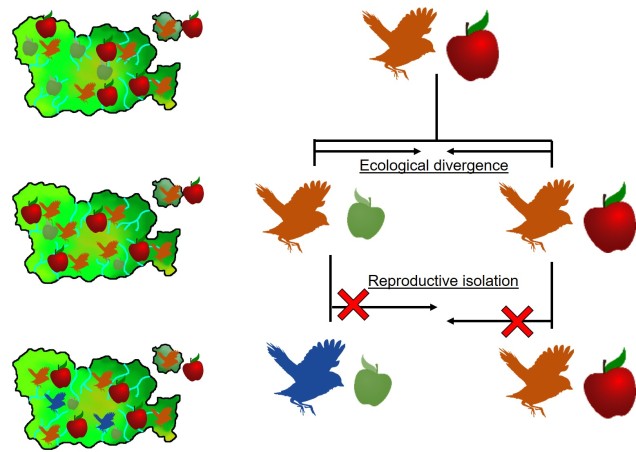

One promising targeted, genetic-based method that has shown great promise is the gene drive. Following some of the theory behind genetic engineering, gene drives are targeted suites of genes (or alleles) which, by their own selfish nature, propagate through a population at a much higher rate than other alternative genes. In conjunction with other DNA modification methods, which can create fatal or sterilising genetic variants, gene drives present the opportunity to allow the natural breeding of an invasive species to spread the detrimental modified gene.

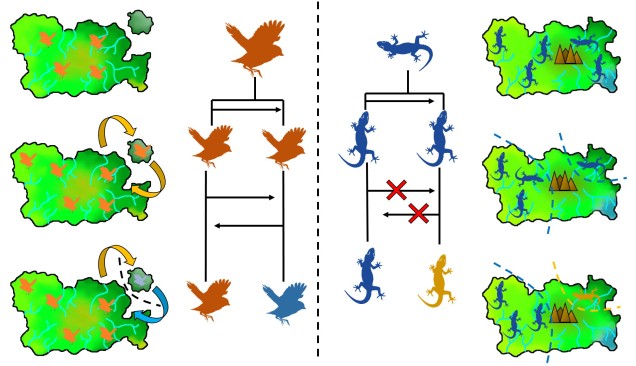

Although a relatively new, and untested, technique, gene drive technology has already been proposed as a method to address some of the prolific invasive mammals of New Zealand. Naturally, there are a number of limitations and reservations for the method; similar to biological control, there is concern for secondary impact on other species that interact with the invasive host. Hybridisation between invasive and native species would cause the gene drive to be spread to native species, counteracting the conservation efforts to save natives. For example, a gene drive could not reasonably be proposed to deal with feral wild dogs in Australia without massively impacting the ‘native’ dingo.

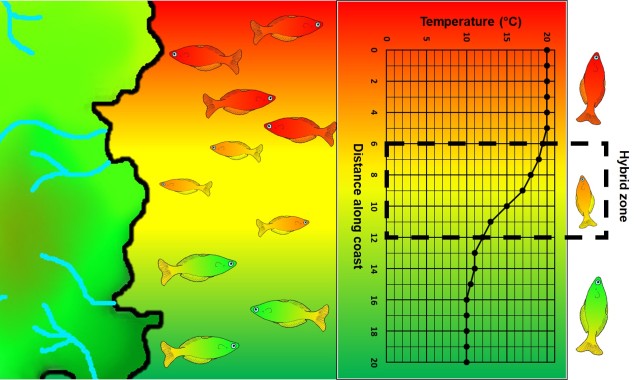

Genes for non-genetic methods

Genetic information, more broadly, can also be useful for pest species management without necessarily directly feeding into genetic engineering methods. The various population genetic methods that we’ve explored over a number of different posts can also be applied in informing management. For example, understanding how populations are structured, and the sizes and demographic histories of these populations, may help us to predict how they will respond in the future and best focus our efforts where they are most effective. By including analysis of their adaptive history and responses, we may start to unravel exactly what makes a species a good invader and how to best predict future susceptibility of an environment to invasion.

The better we understand invasive species and populations from a genetic perspective, the more informed our management efforts can be and the more likely we are to be able to adequately address the problem.

Managing invasive pest species

The impact of human settlement into new environments is exponentially beyond our direct influences. With our arrival, particularly in the last few hundred years, human migration has been an effective conduit for the spread of ecologically-disastrous species which undermine the health and stability of ecosystems around the globe. As such, it is our responsibility to Earth to attempt to address our problems: new genetic techniques is but one growing avenue by which we might be able to remove these invasive pests.