You will have likely seen in the news recently about the ‘de-extinction of the dire wolf’, a canid species which went extinct over ten thousand years ago. Using gene editing techniques and gray wolves, Colossal Biosciences – a for-profit biotechnology company based in Dallas, Texas – claim to have restored the lost megafauna through the production of three genetically-modified wolf pups. To do this, their scientists edited a literal handful (14) genes based on those loosely identified as ‘under positive selection’ in an ancient dire wolf genome. As expected, there are several technicalities which have not been adequately covered by the resultant media fanfare (e.g., that dire wolves are equally close in evolutionary distance to coyotes, dholes and jackals as they are gray wolves). The associated pre-print (i.e., yet-to-be-peer-reviewed), featuring fantasy-writer-but-not-scientist George R. R. Martin, was published on April 11th 2025, resulting in more direct scrutiny by the scientific community.

Contrary to expectations of both a conservation geneticist and this blog, I will not focus on the technical aspects of the ‘research’. These elements have been well-covered by others, including Riley Black and Dr. Jess McLaughlin: to sum, the evidence presented that these pups represent true dire wolves is uninspiringly scant, even from the reductionist position of genomics only. By extension, the criterion of ‘de-extinction’ is clearly not met by the production of three genetically-modified organisms which neither represent nor resemble their supposed ancestors. IUCN Species Survival Commission Canid Specialist Group similarly state that “the three animals produced by Colossal are not dire wolves”, and their ‘resurrection’ “does not contribute to conservation.” That much of the media surrounding the event takes this preposition of de-extinction with presumption speaks to the marketing operations of a biotechnology company far more than it speaks to scientific merit or conservation value of such a program. But I digress.

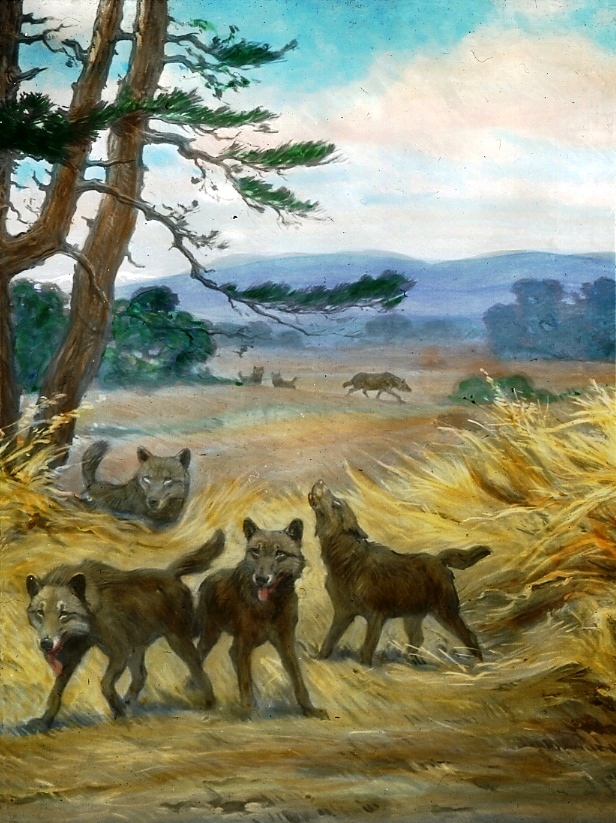

An artistic rendition of a pack of dire wolves by Charles R. Knight, 1922. Source: Jesse Earl Hyde Collection, Case Western Reserve University (CWRU) Department of Geological Sciences.

The ensuing media attraction to the news – and the response of the non-academic public – is what draws my attention. In an age of conservation pessimism, where many species seemingly continue to spiral downwards towards extinction, where endangered species lists swell like the bloated carcass of a whale, optimistic stories are scarce. Promises of de-extinction fill this void, providing a potential light for even the direst (pun intended) of species. A way to unshackle our biodiversity from the looming threat of extinction.

But a core truth of conservation is that extinction is absolute. It is the crisis of the crisis discipline. The knowledge that there is a point of no return – a critical moment upon which the fate of an entire evolutionary lineage may rest, that might define biological legacies millennia in the making – invigorates scientists and managers into action. By acknowledging this point, and the stakes it holds, we draw a clear line-in-the-sand from which to base action.

De-extinction offers an emotionally tantalising alternative: absolution.

This perspective invites us to look backwards, not forwards. To be retrospective rather than prescient. For most species, that will spell their doom. As climate change accelerates, urbanisation transforms entire landscapes, and rapidly changing policies alter our ability to interact with nature, rapid and immediate action is required to prevent further extinctions. But despite the scale of the biodiversity crisis, the cost (and feasibility) of conservation-based action is leagues cheaper and more effective than developing de-extinction technologies for every species that goes extinct. It is both our scientific and moral obligation to act early to prevent ecosystem collapse.

It might seem strange for a conservation biologist to approach de-extinction from an emotional, moralistic perspective. But conservation science – perhaps more-so than other disciplines – requires a deeply emotional stake. Conservation is not an inherently rewarding science: it does not pay as well as other sciences, can be fraught with instability, and can lead to heartbreak despite decades of work. To choose a career in conservation is to feel a moral and ethical calling to biodiversity, to acknowledge the inherent value of the environment and our duty as custodians to protect and conserve it. If you have spoken to a conservationist – regardless of status, position, or employer – I am certain you will have experienced passion and emotionality that drives the field forward. From this stance, I am somewhat empathetic to the allure of de-extinction: that we might be able to un-do our past failures, to ‘right our wrongs’. But as many scientists have argued for many years, the reality of de-extinction (and its capacity to deliver) are far removed from the immediacy and scalability of the biodiversity crisis. We cannot de-extinct our way out of this one.

De-extinction offers absolution from our recent conservation mistakes: like the extinction of the bramble cay melomys, the first mammal extinction to be linked to the climate crisis. Source: Ricardo Macia Lalinde, via The Guardian.

The allure of absolution is not a purely philosophical exercise, either. US Secretary of the Interior Doug Burgum stated via Twitter/X that the ‘dire wolf’ ‘de-extinction’ (of which Colossal Biosciences have neither) “heralds the advent of a thrilling new era of scientific wonder.” In his statement, he claimed that “since the dawn of our nation, it has been innovation – not regulation – that has spawned American greatness.” This statement is a siren call played with alarm bells. A political signal for the justification of de-regulation, for the removal of the very protections that prevent further extinctions. As a consequence, the US administration has proposed a major alteration to the Endangered Species Act which would remove the regulatory definition of “harm” within the act – potentially enabling impacts on endangered species including habitat modification. The perspective that extinction is not final (nor even concerning) has enabled justification of egregious reform that will jeopardise the conservation of thousands of still-extant species.

Others have pointed out the irony that the recovery of the bald eagle – the nationalistic emblem of the American people – was enabled by regulation. By 1963, only 417 breeding pairs of bald eagles were known to exist in the wild: in 1967, the species was listed as Endangered under the Act. The primary culprit – secondary impacts of dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT), a powerful insecticide used to control pests in agricultural landscapes. The subsequent pollution of DDT into waterways impacted aquatic plants and fish and found its way through the food chain to bald eagles. DDT impacts caused bald eagle eggs to become thin and brittle, often failing to hatch or breaking during incubation. As a result of the impacts, which became widely known due to the book “Silent Spring” by Rachel Carson, the Environmental Protection Agency banned the chemical in 1972. In the following decades, bald eagle population numbers across northern America have rapidly increased: in 1995, the species was downlisted to Threatened and removed from the list altogether in 2007. Current estimates place the total bald eagle population at over 300,000 birds. Regulation, protection, and legislation have saved countless species from extinction, and will continue to be a critical backbone for effective conservation management. De-extinction will not substitute regulation and immediate action in the prevention of extinction.

The bald eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) was saved by regulation – no de-extinction required. Image credit: USFWS Midwest Region.

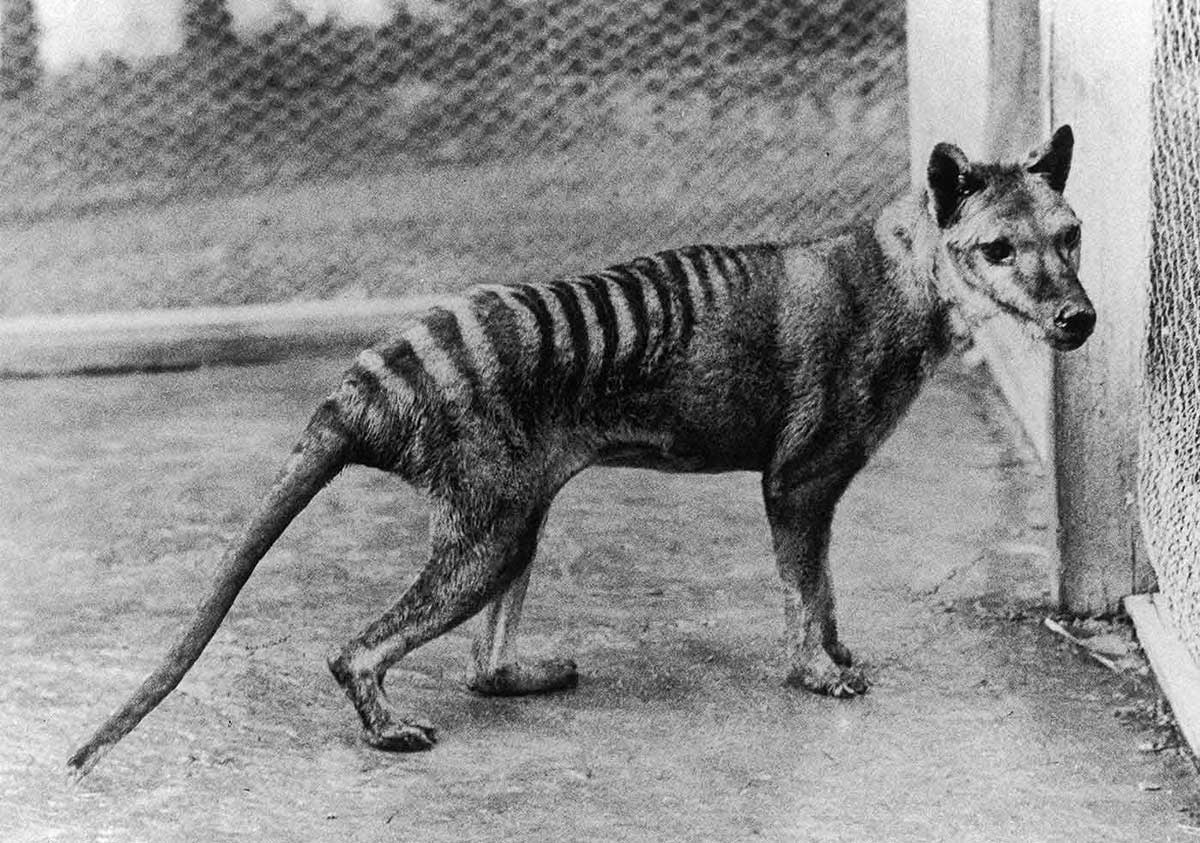

The appeal of de-extinction – particularly in the way that it is touted – is in absolving ourselves of our past conservation mistakes. In Australia, this is best exemplified by Colossal Biosciences attempts to de-extinct the thylacine, the last animal of which died in 1936. On September 7 every year, Australia acknowledges National Threatened Species Day in the wake of the death of the last remaining thylacine. The loss of the species creates a remarkable ecological gap within Tasmania (and arguably the rest of the country, but somewhat more controversially), and I believe that there are noble ecological and emotional reasons for attempting its de-extinction. But we must face the reality of our past mistakes, acknowledge the consequences of our actions, and address them moving forward – only by learning from the heartbreak of these failures can we hope to protect the rest of our endangered fauna and flora.

An photograph of the last known living thylacine, in Beaumaris Zoo, Hobart (~1936).

”This statement is a siren call played with alarm bells. A political signal for the justification of de-regulation, for the removal of the very protections that prevent further extinctions.”

so much yes to this. Thank you G-cat.

LikeLiked by 1 person